But two major roadblocks exist to realizing the benefits from new data sources. First, cooperation between information systems/technology specialists and accountants to develop information systems has diminished in recent years. This presents a problem because IS/IT specialists have in-depth knowledge of data and technology, but accountants know best how to use it. The lack of cooperation means there’s an increased risk of capturing unneeded data or failure to capture the right data. Second, there’s an absence of expertise in data analytics among accountants even though they possess the broadest knowledge of business activities, which provides valuable contextual knowledge for data analysis. But without a good understanding of data and analytical tools, accountants can’t fully make use of this advantage.

The amount of data that’s available, and the speed at which it’s accessible, allows older, more summarized accounting information to be replaced by newer, more granular, and often more understandable information. This has led to recent efforts by many organizations to acquire data analytics expertise. An important question for employers is “Where will this expertise reside in the organization?” The answer: within the accounting-finance function.

These new developments provide exciting opportunities for accountants, especially management accountants, to alter and expand their roles into both systems development and data analytics. This will require adopting a new view of information systems and a willingness to accept new training in business technology tools to help them to handle and analyze data and present key information.

Organizations need to begin preparing their accountants to serve in these new capacities. Here’s a closer look at what needs to be done.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES, NEW PERSPECTIVES

Technology is changing faster than business practice or education can keep up. New storage, data analysis, and cloud computing tools have facilitated the creation, collection, and use of Big Data. This shift has led employers, particularly in public accounting, to call for accountants to increase their understanding of current technologies and data analytics. As a result, companies are increasingly looking for people with expertise in Linux, OpenStack, NoSQL, Apache Hadoop, and Apache Spark. A solid understanding of these technologies would enable accountants to collect, transform, analyze, and visualize data.

As principal custodians of business information and reporting, management accountants must increase their ability to communicate with and assist IT teams. As a number of experts have noted, the current status quo is to hire information systems students to perform even the most menial IT audit and data analysis tasks because accountants lack the relevant knowledge. Yet if accountants continue to not learn IT skills, IT specialists might learn theirs and replace them.

So what’s the answer? For starters, business professionals and educators need to adopt a new perspective on the information systems landscape in order for these skills to be incorporated effectively. To that end, we offer a new framework for accounting information systems that we call Accounting Architecture. This framework combines knowledge across the disciplines of accounting and information systems, information technology, and computer science to provide a unified view of what constitutes accounting information and explains how financial, tax, and management accounting; audit and internal controls; business intelligence; programming; and IT fit into one system. This is an exciting time in that accountants who possess IT and data analytics expertise can occupy a unique position to help guide corporate strategy by creating a link between business activities and the IT functions that support these activities.

Currently, accounting education focuses heavily on regulation and compliance. Although accountants certainly need to have a broad understanding of the rules, this focus fails to instill in students an understanding of the information system as a whole. Even the courses that teach topics other than accounting rules and regulations, such as management accounting and accounting information systems, emphasize business cycles and cost formulas at the expense of providing perspective into the process of data becoming information.

Because employers have begun to demand new skills of accountants, professional organizations like IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) should continue to encourage and work with the university community to reevaluate the current model for accounting information systems and the encompassing curriculum to determine what revisions are necessary to train accountants.

But let’s not act hastily lest we miss the mark. For example, one of the problems with the earlier wide adoption of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems was that companies felt an urgency to have one. Unfortunately, they turned out to be useless for organizations that didn’t understand their own information needs. This same fever now exists for Big Data. But in order for any modifications or additions to an information system to be useful, there must be an understanding of the system as a whole. This further serves as a call to employers to carefully consider what training and education are needed to best serve their organizations.

OLD AND NEW MODELS OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Open a textbook on current accounting systems and you’ll see that it includes three processes (data collection, data processing, and information reporting) and one object (data storage) while excluding many aspects of systems that are important today (see Figure 1).

While that old model worked well for a number of years, a revised curriculum will provide accountants with broader knowledge concerning key elements of an information system and their relationships as well as with the skills to meet employers’ current expectations. Accountants should be able to assist in systems design, maintenance, and audit, but to succeed they’ll need to be knowledgeable about the physical IT infrastructure, which involves a lot more than data storage. Accountants should know about these additional IT components and how to interact with and audit them.

With respect to data analytics, the revised model should include the technologies needed to convert structured and unstructured data into useful reports with multiple analytical tools.

Because information security is a primary focus of an organization’s controls, a revised view should include internal controls and the various ways that technology promotes data security.

A data-driven view of accounting systems that’s more consistent with modern information technology is shown in Figure 2. The arch represents the components of an information system, and within each group are multiple building blocks that subdivide these components into their relevant constructs. As the most important component, Information sits at the top of the arch. Technology and Control are the legs because they play supporting roles by providing the tools to create, store, and analyze data as well as the controls to maintain data security and integrity. Finally, at the base of the arch is the foundation, which comprises the constraints of a useful information system. Naturally, the specific content within the individual blocks will vary depending on circumstances.

This new model extends the traditional view of accounting information systems in several important ways. First, the Information section of the arch portrays the activities in the information life cycle in three nonlinear groups: creation, use, and maintenance. Creation comprises needs assessment, data acquisition, classification, conversion, and data entry; Use includes searching, data analytics, and reporting; and Maintenance involves storage, organization, indexing, rights management, refreshing, interpretation, and disposition (data disposal). Of course, in order to understand an information system, we must also understand the process by which data becomes information and how information should be managed.

Second, the addition of technology within the framework serves to combine information life-cycle principles with the physical IT infrastructure, which represents the application of information system principles. Learning applications permit accountants to use real-world tools to bring principles into practice.

Third, this model explicitly includes control activities to support the information system. Internal controls are paramount to accountants, and a primary focus of control activities is information security. An understanding of this role of internal controls is necessary in order to train IT auditors and analysts.

Fourth, by including compliance and the business model in the foundation, the model links the information system with accounting rules and business cycles as currently taught in accounting curricula. The ability to perceive this link will allow accountants to view financial, tax, and management accounting; audit; the information system; and the IT infrastructure as belonging to one unified system instead of disparate sets of regulations, policies, and practices.

Fifth, because innovation constantly changes information technology, any accounting information system model must allow for relevant changes to the technological landscape. Our education model identifies blocks that are necessary components of a controlled, well-defined information system, although the precise implementation may vary.

The Accounting Architecture framework in Figure 2 is a roadmap for organizations to develop structures for systems development and reporting and for accounting educators to align teaching with practice. Revising the accounting curriculum would redirect attention from business cycles toward teaching the principles of the information life cycle. Internal controls are explained within the context of information security instead of business cycle security, and the curriculum would provide an understanding of and practical experience with enterprise-grade programming languages, operating systems, databases, and data analysis tools. Because the Accounting Architecture model encompasses information systems and accounting regulations, a revised curriculum could begin with an introduction to Accounting Architecture—even before teaching accounting standards—so that all accounting education could be cast within the context of a single unifying framework.

A LOOK INSIDE THE ARCH

As management accountants, you’ll want to know more about each major segment and component block of the arch before you can judge its true value and utility. With that in mind, here’s a brief explanation of the key elements. Some of the information may seem basic, but it’s always good for a reference.

The three blocks that establish the arch’s foundation are compliance, business model, and technological feasibility. Compliance is the most familiar to accountants, who understand the need for information systems to generate reports for external stakeholders even though internal decision makers are their primary consumers of information. These decision makers select the business model—the set of business activities and firm structure—and the information system measures and reports on these activities. Technological feasibility dictates that the desired information system must use existing components. Because business models and informational needs are idiosyncratic, however, many firms have increased in-house software development to create innovative information systems while still making use of open-source software.

Though it may sound obvious, the primary focus of any information system is information, which means that accountants should understand the process by which data becomes information. This is traditionally the domain of information science and the key to proper design, maintenance, and audit. We’ve subdivided the steps of the information life cycle into three blocks: creation, use, and maintenance, each of which is composed of multiple activities.

Creation. Needs assessment is used to determine informational or reporting needs as governed by the business model and compliance blocks. Data acquisition is the receipt of data from a counterparty. Classification is the process of assigning identifying characteristics in order to avoid data being collections of seemingly arbitrary characters that neither a human nor a computer can read.

Use. The pinnacle of the information life cycle is the use of data to disseminate information. Searching, analysis, and reporting are the primary activities that transform data into useful information. These steps jointly constitute business intelligence. Management accountants need to know about analytical tools and be able to explain the models behind them. Data visualization techniques are important so that systems designers can increase the value and readability of reports.

Maintenance. Maintenance governs data storage, organization, indexing, and disposition. Both the business model and compliance dictate many aspects of a maintenance plan, but some aspects simply constitute best practices. For instance, storage can be as simple as a filing cabinet for source documents and printed reports or as complex as databases, shared flat-file systems, and version control systems for digital data. Storage repositories must be scalable to accommodate data creation without having to dump files to clear room for stored data, organized to increase findability, indexed to decrease search time, and tailored to increase both data usefulness and compliance. Data should have a predetermined end of life similar to the useful life associated with depreciable assets and should be disposed of accordingly.

THE TECHNOLOGY AND CONTROL LEGS

The first leg of the arch is Technology, or the IT infrastructure. Its four components are hardware, software, storage, and services. Accounting students’ current training in this area typically includes little discussion of information technology, despite employers’ desire to hire accountants with IT knowledge. As a result, accountants have a poor understanding of operating systems, server and network equipment, and enterprise-grade databases and software. Thus they can’t participate in many IT audit functions, systems design and maintenance, database administration, and end-user software development. More extensive education will allow them to bridge the gap between business knowledge and IT.

Hardware. While no one expects them to be the next Steve Jobs, management accountants should be familiar with the basic building blocks of a computer: central processing units (CPUs), random-access memory (RAM), motherboards, graphics processing units (GPUs), and storage drives. Areas of knowledge should include trade-offs between fat clients (individual workstations) and thin clients (networked computers), server hardware, and network infrastructures to facilitate data collection and communication.

Software. If they know nothing else about software, accountants should keep these three things in mind: First, hardware is useless without software. Second, virtualization (think “the cloud”) has allowed software to act as hardware, reducing the cost of and reliance on hardware. Third, relatively little variation exists between the hardware components of various networks, whereas software—especially software developed in-house—can offer unique capabilities and benefits. Knowledge of operating systems (Microsoft Windows, Apple macOS, Linux, Unix, BSD, etc.), as well as web applications and business intelligence solutions (SAS Visual Analytics, Tableau, Splunk, CaseWare IDEA, ACL, etc.), is also important.

The current frontier of technological innovation will strongly influence whether your organization decides to develop software in-house. Open-source software offers a recent alternative to proprietary or in-house-developed software. Like it or not, accountants are going to need to know about open-source software and software development methodologies so they can support these activities.

Storage. Accountants should be able to speak intelligently about choices concerning database structure, file systems (including version control systems), and administration techniques. This means they’ll need an understanding of multiple RDBMS (relational database management systems), and at least a cursory knowledge of SQL (structured query language), in order to participate in systems design, maintenance, audit, and data analytics activities. NoSQL (Not Only SQL) databases are a popular alternative for handling internet traffic and Big Data.

Services. The most prominent aspect of outsourced IT services is cloud computing, which represents a return to the decades-old client-server model and is a major part of enterprise-grade information systems. Although many public clouds are offered and managed by third parties, the proliferation of in-house, private clouds should encourage accountants to understand cloud components as well as the implications of the select service level: Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), Software as a Service (SaaS), Database as a Service (DBaaS), etc.

With technology leading the way, Control preserves data integrity by avoiding unauthorized access, loss, and error. The blocks in this section mirror the elements of the Trust Services Framework for systems reliability: security, availability, processing integrity, and confidentiality. These four components combine to support information security and data integrity and to prevent data leakage. We include them in the Accounting Architecture framework to emphasize to students the importance of information security and information system reliability, which experts rank as primary goals of control activities.

EDUCATION THAT KEEPS PACE WITH TECHNOLOGY

Unfortunately, business education is often painfully slow to deliver content consistent with business reality. Higher education needs encouragement from employers and professional organizations to enact change. Also, employers must show how students with these skills will thrive within their organizations.

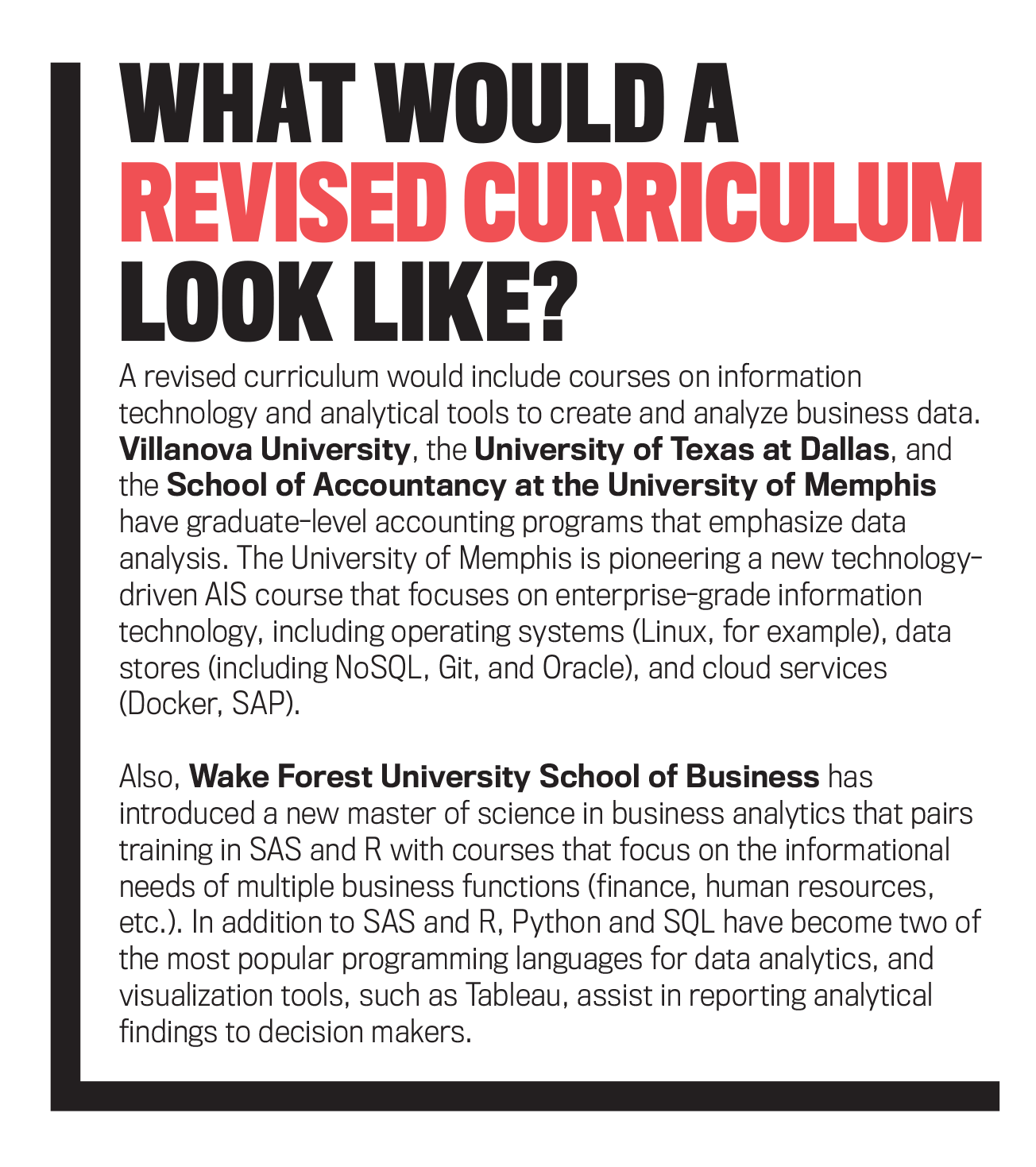

We offer two proposals for changing accounting education to conform to these new realities. The first proposal calls for changes to the undergraduate curriculum, and the second addresses graduate programs. But the proposals aren’t mutually exclusive. In both instances, internships targeted to students interested in information systems and data analysis will provide valuable experience and support for a new education model.

The rapidly changing landscape of information systems technology will likely discourage the use of traditional textbooks as a foundation for these courses. As an alternative, trade publications (like the one you’re reading right now) and articles from popular news outlets may be more effective to educate individuals regarding new technologies, adoption trends, developments in data analytics, and security and internal control practices.

Possible Changes to Undergraduate Accounting Courses. Currently, introductory accounting courses teach financial accounting regulations and managerial accounting formulas without giving students a perspective of the information system as a whole. The Accounting Architecture framework expands the scope of accounting information and puts it into context with regulatory compliance, the business model, and the information system. If the curriculum included a required course that introduced the Accounting Architecture framework first, students would be better able to grasp the importance of accounting standards. This introduction would briefly survey the constructs in the arch, discuss sample business processes to demonstrate how an information system might work in practice, and present a roadmap of accounting courses and their relation to the model. This course would give students a better understanding of the accounting curriculum, permit more extensive coverage of systems later in the undergraduate curriculum, and may increase interest in the accounting profession overall.

Possible Changes to Graduate Courses. Some universities have begun investigating, or have already implemented, accounting master’s tracks or emphases in either data analytics or IT audit. An introduction to the Accounting Architecture framework exposes students to aspects of both fields and to systems design. The overlap in content in these areas, as well as commonality in professional roles, encourages implementation of a single track for study of Accounting Architecture. For example, internal audit departments use data analytics to detect problems. The link between systems design and systems audit is even more intuitive. Yet the goal in both cases is to determine how a system should function. Accountants are already familiar with this duality because financial preparers need the same knowledge as financial auditors, and tax preparers need the same knowledge as tax auditors.

Graduate students should have courses in relational databases and advanced data management topics, including NoSQL, data warehousing, and online transaction processing (OLTP). Additionally, we suggest exposing students to enterprise-grade operating systems (Unix and Linux) and database management systems (Oracle, MySQL, Apache Cassandra). Because of an increase in in-house software development, we also propose that students learn about open-source software and current software development methodologies, especially DevOps. Not all of these experiences have equal value, but each exposes students to technological components of most enterprise-grade information systems.

The final portion of the curriculum includes courses in business intelligence and data analytics. These address the use of information and involve skills that are in high demand. Information systems departments frequently teach business intelligence, and, with the current focus on Big Data, some departments have also introduced a course in data analytics.

These proposals provide an overview of the courses relevant to preparing a student to become an accounting architect. Because of the dynamic nature of IT, the list of relevant topics and skills will certainly change in the future, and the curriculum should be flexible enough to accommodate these demands.

WHAT THE FUTURE MAY HOLD

Employers demand new skills in systems design, data analytics, and IT audit. The current perspective of the accountant’s role in systems design and reporting is based on a dated model, which must be modified in order to train accountants to serve in 21st Century organizations. The Accounting Architecture framework reflects employer requirements that suggest revisions to undergraduate and graduate accounting education toward the information life cycle, information technology, and information security. This new framework gives a unifying perspective of accounting that can (1) help employers think about how to cultivate and organize new skills and responsibilities for delivery of information system and reporting services and (2) help students better understand information, information systems, and how accounting standards affect the organization’s information needs.

Data is more widely available than ever before. Ultimately, granular data will be accessible to everyone, potentially diminishing the role of summarized financial reports. Decision makers will increasingly rely on data that’s easier to understand and that can substitute for summarized financial information. This view corresponds with employers’ demands for individuals with data analysis and presentation skills.

There already are business and information systems architects who serve as experts in business and IT processes, respectively. Now it’s time to prepare and introduce accounting architects who can serve as experts in the creation, use, and maintenance of accounting information. Management accountants are best equipped to fill this role and can do so admirably if they receive the right education and training. Are they ready, and will they take on the challenge?

March 2017