Rising healthcare costs are a major global challenge. A number of factors contribute to this trend, including aging populations and medical technology. But an underlying and misunderstood source of healthcare’s escalating costs has been the inability of healthcare provider organizations (such as large medical centers) to properly measure and manage the true costs and value of healthcare.

How can healthcare provider organizations find better ways to measure and manage healthcare costs and value to achieve improved outcomes and lower costs? Let’s take a look.

MICHAEL E. PORTER is Bishop William Lawrence University Professor and director of the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness, faculty chair of “Creating Shared Value” and “Strategy for Health Care Delivery,” and faculty cochair of “Value Measurement for Health Care” at Harvard Business School. He is recognized as the leading authority on strategy and competitiveness, and his work influences chief executive officers and government leaders throughout the world. He is the author of 19 books, including Competitive Strategy, Competitive Advantage, Competitive Advantage of Nations, On Competition, and Redefining Health Care, and more than 125 articles. He has won many scholarly awards and honors including the Adam Smith Award of the National Association of Business Economists, the John Kenneth Galbraith Medal, the David A. Wells Prize in Economics from Harvard, and the Academy of Management’s highest award for scholarly contributions to management. He is also an unprecedented seven-time winner of the McKinsey Award for the best Harvard Business Review article of the year. In 2000, he was named a University Professor by Harvard University, the highest recognition that can be awarded to a Harvard faculty member.

ROBERT S. KAPLAN is Senior Fellow and Marvin Bower Professor of Leadership Development, Emeritus at Harvard Business School. He is currently collaborating with Michael Porter on Value-Based Health Care, especially measuring the cost of delivering healthcare and introducing bundled payments to incentivize better patient outcomes and lower costs. He is codeveloper of both activity-based costing (ABC) and the balanced scorecard (BSC) and is now extending the use of strategy maps and BSCs for interorganizational collaboration. He has authored or coauthored 14 books and more than 175 articles, including 25 in Harvard Business Review. His books include The Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Advantage, the fifth balanced scorecard book coauthored with David Norton, and Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing with Steve Anderson. Elected to the Accounting Hall of Fame in 2006, Kaplan received the Lifetime Contribution Award from the Management Accounting Section of the American Accounting Association (AAA) in 2006, the Lifetime Contribution Award for Distinguished Contributions to Advancing the Management Accounting Profession from IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) in 2008, and the IMA Distinguished Advocate Award in 2016.

MARK L. FRIGO is Ledger & Quill Distinguished Professor of Strategy and Leadership in the Driehaus College of Business at DePaul University and director of the Center for Strategy, Execution and Valuation where he leads research on high-performance companies in the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business at DePaul. He is the author of seven books, including DRIVEN: Business Strategy, Human Actions and the Creation of Wealth (with Joel Litman), and more than 100 articles in leading business journals including Harvard Business Review.

TAKING ON A CHALLENGE

Frigo: Healthcare is obviously a very important and challenging area to study. As two Harvard Business School professors, why did you decide to address the issue? How did you start working on this together?

Porter: One of my strategy colleagues, Elizabeth Teisberg, had several unhappy encounters with the healthcare system. In our discussions, it became clear that this industry was competing differently from all the other industries we study and teach about in the strategy area. Healthcare is an industry with many and diverse competitors, a situation that generally leads to vigorous competition in which companies win by producing the best value for customers. In contrast, healthcare enterprises survived and succeeded even when they were high-cost and didn’t deliver good outcomes for customers. As we examined healthcare more deeply, we concluded that we needed to change the nature of competition so that it would reward those who delivered the highest value for patients; we defined value as better outcomes achieved at lower cost. We first described the necessary transformation in a 2006 book, Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Since that time, I have been joined by colleagues such as Dr. Thomas Lee, Dr. Thomas Feeley, and Bob Kaplan to build the tools and concepts to put the Value-Based Health Care (VBHC) agenda into actual practice.

Kaplan: Michael called me in 2010. He told me that measuring costs correctly at the medical condition level was a central component in his agenda to transform healthcare delivery in the United States and globally but that none of the provider organizations he had been working with seemed to measure costs in ways that made sense to him. His insight was correct since existing healthcare cost-measurement approaches were not following proper cost accounting principles. I responded with my belief that time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) would work well in healthcare, but I had never found any hospital administrator or clinician willing to try it out. Mike indicated that he knew of a few hospitals and clinicians who might be good candidates for pilot projects and asked whether we could work collaboratively on this issue. I readily accepted, and from that emerged a great partnership between us.

I now realize that TDABC couldn’t have been introduced successfully without the outcome measurements that Mike was advocating since managers and clinicians would be properly concerned that cost reductions could compromise patient safety and quality of care. By measuring costs accurately at the medical condition level, along with good outcome metrics, we had the proper foundation for the entire edifice of VBHC to become implementable.

IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS

Frigo: What are the most important contributions that management accountants can make to this area?

Kaplan/Porter: For far too long, healthcare delivery has been a “fact-free” zone, with missing, incomplete, or distorted measurements of performance. Management accountants can play a critical role by championing tools to produce better, more valid measurements of healthcare outcomes and costs at the right unit of analysis. These new measurements will have a transformational impact on value creation and will stimulate healthy competition in the sector.

Management accountants can play an important role in focusing and aligning the myriad continuous improvement programs now under way at many provider organizations. They need to ensure that these programs produce tangible value improvements, quantified as superior outcomes and lower costs. Better measurement will also enable new payment models that reward providers who deliver higher-value healthcare. Management accountants should be part of the team that designs and implements value-based payment models, especially bundled payments covering comprehensive treatment of a patient’s medical condition linked to strong accountability for patient outcomes.

VALUE-BASED HEALTH CARE DELIVERY

Frigo: Your work on Value-Based Health Care Delivery (VBHCD) explores ways to improve value for patients, improving processes and reducing costs without sacrificing outcomes. What tools and approaches do you apply in this area to help healthcare provider organizations create greater value?

Porter: We define value improvement as better patient outcomes relative to the costs of achieving them. With this central goal, healthcare enterprises need to measure and be far more accountable for patient outcomes. Unfortunately, the healthcare field has gotten confused about the differences between outcomes and processes of care. In the pursuit of quality, healthcare has become overly focused on introducing checklists and measuring compliance with evidence-based protocols rather than achieving better patient outcomes. Measuring processes is important and useful, but backward-looking process compliance is inadequate to drive transformational value improvement in healthcare.

The single most powerful step to improve health outcomes is to just start measuring them at the level of patients with a given medical condition—such as breast cancer or knee or hip arthritis—or in delivering primary and preventative care for patient segments such as healthy adults. The act of measurement will improve outcomes better and faster than any single new surgical technique, medical device, or drug. For example, a traditional cancer care outcome measurement is the five-year survival rate. But five-year survival rates for many cancers are improving, and in some cases are already high, so this alone won’t differentiate high-performing vs. low-performing institutions. Our work with MD Anderson Cancer Center has highlighted the importance of measuring the functional status of patients after treatment. For example, head and neck cancers affect the vocal cords and swallowing. MD Anderson now measures the proportion of its head and neck cancer patients who retain the ability to speak normally, without a voice box, and how many can regain the ability to eat normally without having to use a feeding tube.

Another example of the need for multiple outcome measures is prostate cancer. If after surgery or radiation treatment the patient is incontinent and impotent, he isn’t likely to feel that the treatment was a complete success. Similarly, a patient receiving a total knee replacement in which her surgeon followed all the correct protocols and no infections or readmissions occurred won’t think it’s a success if she can’t ride a bicycle or walk a golf course because of residual pain.

If we’re to unlock the potential of value-based healthcare for driving improvement, outcomes measurement must accelerate. That means measuring a sufficient set of outcomes for every major medical condition—with well-defined methods for their collection and risk adjustment—and then standardizing them. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), which I cofounded, convenes groups of global experts on specific conditions together with patient representatives to define minimum standard outcome sets and risk factors for each medical condition. ICHOM has published more than 20 sets covering about 45% of disease burden in the U.S. and other high-income countries, and there are many more to come. The international nature of the effort has allowed participants to see that patients with a given medical condition have similar needs everywhere. These outcome standards are putting providers, payers, patients, and information technology vendors on a common path for tracking what needs to be tracked and making implementation of outcomes measurement easier and more efficient.

Our experience has been that tracking and reporting outcomes leads to much better performance and much lower variability in outcomes. Clinicians have great professional pride and commitment to their patients, which are powerful motivators for them to improve outcomes. But when patient-level outcomes aren’t measured, as they haven’t been for centuries, all physicians live in Lake Wobegon (a fictional town created by storyteller Garrison Keillor) in which none of them is below average even though 50% of them must be.

PROPER MEASUREMENT IS A CRITICAL FIRST STEP

Frigo: Your research with healthcare provider organizations indicates that traditional cost-cutting initiatives can actually lead to higher costs and lower-quality care. Why is the proper measurement of healthcare costs so critical for improving healthcare value? What are the common mistakes made in cutting costs at healthcare provider organizations?

Kaplan: Historically, costing in healthcare organizations was done in idiosyncratic ways, reflecting healthcare’s special circumstances. Provider organizations—hospitals, clinics, and physician practices—estimated costs based on charges. They used methods such as the ratio-of-costs-to-charges (RCC) or costing based on relative value units (RVUs) that had been developed for pricing hospital and physician services. Also, only reimbursed services were costed. The costs of nonreimbursed services were buried in arbitrary-allocated overhead pools. Finally, costing was applied to departments and procedures but not to all the services involved in treating a medical condition over the patient’s full cycle of care.

Because costing systems were so muddled, the only reliable information for hospital administrators came from the line-item income statement, which is organized by spending category, not by medical condition. Senior managers knew how much they were spending on employees, equipment, devices, imaging, laboratory tests, and pharmaceuticals. So in cutting costs, their tendency was to impose arbitrary cuts at the line-item level, such as “put a cap on our spending on drugs” or “implement a 10% across-the-board cut in personnel costs.” These types of arbitrary spending reductions are likely to harm patient outcomes and won’t be sustainable.

The only way to achieve sustainable cost reduction is to understand the structure of delivery itself, which requires looking at how an organization is currently spending money to treat patients for specific medical conditions. This allows identifying the inefficient and ineffective processes (those not contributing to better outcomes), understanding whether the right type of employee is performing each process step, and so on. With this information, providers can make fundamental process improvements that enable them to accomplish the same amount of work or better, with fewer or less expensive resources and without harming outcomes. That is where sustainable cost reductions must come from.

Today, clinicians and administrators are “flying blind.” They have no visibility into the clinical and administrative processes used to treat each medical condition. As a result, they have no way of systematically pursuing cost-reduction opportunities. By default, they revert to crude, hatchet-like approaches, such as generic high-cost areas (readmissions), or slashing spending across the board. This may eliminate some fat, waste, and inefficiency, but it will also cut into muscle and bone, which compromises the provider’s delivery capacity and quality of care.

Frigo: The Value-Based Health Care Delivery (VBHCD) initiative at Harvard Business School engages with leading healthcare provider organizations to measure and manage patient-level costs over complete cycles of care for a variety of medical conditions. How is time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) being used in this initiative?

Kaplan: TDABC, even though it was developed for manufacturing, retailing, financial, and distribution companies, has turned out to be the ideal way for costing healthcare services. TDABC enables provider organizations to estimate accurately the costs of ALL the resources they use to treat a patient’s medical condition over a complete cycle of care. The concept has been easy to explain and has been readily and enthusiastically adopted by clinicians because it makes sense to them. They can immediately see how it empowers them to take decisive actions that lower treatment costs while maintaining, and usually improving, patient outcomes.

We have conducted several multisite studies where we compared the costs (and outcomes) of treating the same medical condition across different sites. I was astonished to see, even among high-volume facilities, a more than a 2:1 ratio between providers at the 90th and 10th percentile of costs. We then use variance analysis, another standard management accounting tool, to isolate how much of the cost difference is due to the price variance (providers paying different amounts to their personnel and suppliers) and how much is due to an efficiency or productivity variance. Even with the same standard prices for each type of personnel inputs, almost all of the 2:1 ratio in costs persists between inefficient providers (those at the 90th percentile) and efficient ones (those at the 10th percentile). The easiest way to cut costs without harming patients is to learn and transfer the best practices from more efficient organizations to those currently above the median in costs and inefficiency. This is obvious, simple, and quick. But until recently, we lacked valid cost measurements to even know who were the most and least efficient. This was part of the “fact-free” zone in contemporary healthcare delivery. What an amazing sector for management accountants, with experience and expertise in costing, to make important contributions!

PILOT STUDIES SHOW DRAMATIC IMPROVEMENTS

Frigo: Your work on pilot studies with healthcare provider organizations has found some dramatic improvements in cost, outcomes, and value. Can you describe an example or two?

Kaplan: In our joint-replacement work, we found that some surgical groups discharged 90% of their patients for home rehabilitation, which costs about $1,000, while others discharged less than 50% for home rehab, with the remainder sent to skilled nursing facilities, which costs more than $6,000 per patient. And the outcomes were better when rehabbing at home. We studied the groups that discharged a much higher percentage to home and learned that they were doing some simple things that were easy to transfer and replicate at the other sites: more counseling of patients and families at the initial visit, a different pain management approach so that patients could start walking sooner after the surgery, and starting physical therapy earlier. These actions also led to 20% shorter lengths-of-stay (LOS) in the hospital. Within only a few months, the high-cost providers were able to decrease LOS and increase their discharge rate to home health to the 90% level, a true triumph for VBHC: much lower costs and better outcomes.

We also found that the surgeons who could schedule two operating rooms were twice as productive as those who could access only one. When we inquired why all surgeons couldn’t quickly switch from one patient to the next, we learned that many CFOs were reluctant to dedicate two of their most expensive rooms to a single surgeon. This is where good cost accounting is so powerful. A fully equipped operating room costs about $0.50 per minute, whereas a skilled surgical team costs more than $20 per minute. With this data, you don’t need an MBA to figure out which resource—operating rooms or surgical teams—you want fully utilized.

In kidney failure patients, the medical evidence is clear that dialysis is best started after the patient has microvascular surgery to install a fistula or graft, which takes 45-60 days to mature. Yet more than 50% of kidney failure patients today start dialysis with a catheter, which leads to infections and complications that cost, on average, an extra $20,000 over the first six months. A nephrologist told us that if he could spend about 30 minutes more counseling his chronic kidney disease patients on the benefits of the microsurgery, he could dramatically reduce the percentage of patients starting dialysis with a catheter. But the pressure from a false productivity measure—number of patients he saw per day—prevented him from having this conversation. This is absurd. A $100 conversation (30 minutes with a physician whose cost per minute is about $3) is considered unproductive even when it leads to $20,000 in cost savings.

These are just a few of many, many examples about how inaccurate or even absent cost measurements prevent sensible actions that deliver better outcomes at far lower costs. The benefits from valid cost and outcomes measurements, when combined with new value-based payment methods, will transform the economics of the healthcare sector.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Frigo: What do you hope will be the future positive outcomes from your work?

Porter/Kaplan: We are already seeing rapid global diffusion of value-based healthcare principles. We hope, over the next five years, to have generally accepted standard outcome measure sets for medical conditions that cover 90% of the world’s disease burden. Measuring and reporting risk-adjusted outcomes by provider for each of these medical conditions will trigger enormous improvements in the treatments of patients. More patients will be seen by those organizations producing the best outcomes, and fewer will be seen by those delivering poor outcomes. Just this shift in mix raises average outcomes dramatically.

We also hope that providers embrace the discipline of mapping processes for all their care cycles at the medical condition level. This will enable them to benefit from using TDABC to measure and then improve the costs of treating patients over complete care cycles.

With both outcomes and cost measurements in place, we expect that bundled payments will become the dominant payment mechanism. A bundled payment is a single payment that covers all the care for a patient’s medical condition and treatment over a specified time frame. It’s the way we pay for all the other goods and services we purchase. Well-designed bundled payments will enable providers with the best outcomes and lowest costs to be rewarded and to expand their volume. Those unable to deliver superior outcomes at low cost will have to exit the treatment of patients for that medical condition. This dynamic won’t just bend the cost curve—it will actually lower total costs while allowing patients to experience better outcomes. That would be great progress.

RADAR CHARTS: COMPARING OUTCOMES AND COSTS

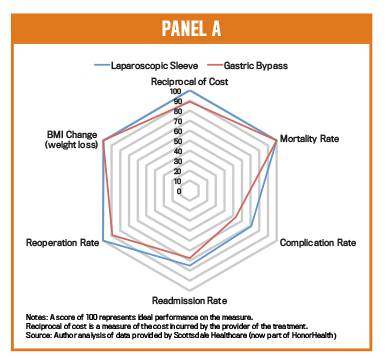

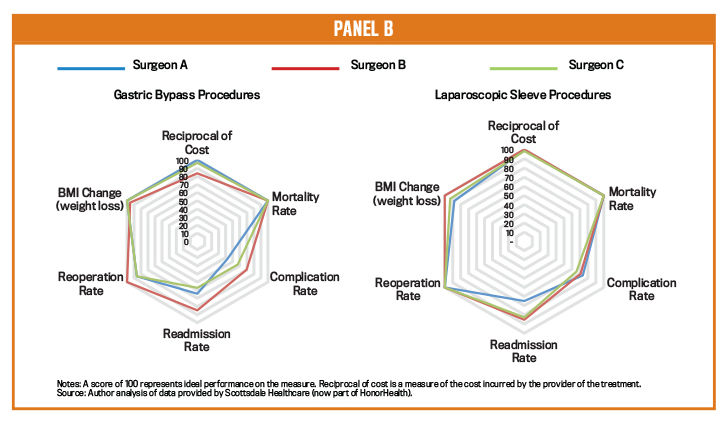

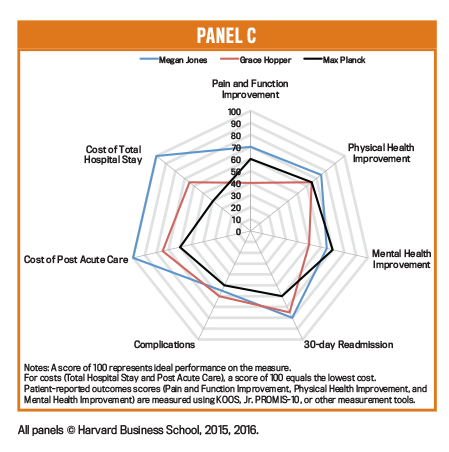

A radar (or spider web) chart can be used to illustrate the Value Framework. Its visual depiction of outcomes and costs on the same chart offers clinicians, managers, patients, regulators, and policy makers an easily understood snapshot of value. They can compare outcomes and costs of different therapies, facilities, and clinicians treating the same medical condition.

Panel A, based on data from Scottsdale Healthcare (now part of HonorHealth), compares the value of two alternative surgical treatments for obesity: Laparoscopic Sleeve and Gastric Bypass Surgeries. The outcomes data for each treatment is graphed on separate axes, scaled from 0 to 100. Cost is plotted as the reciprocal of actual costs (according to time-driven activity-based costing) so that points farther from the center always represent better lower costs. From this data, Laparoscopic Sleeve surgery dominates Gastric Bypass; it offers comparable or better outcomes on all relevant dimensions and is lower cost. This visual rendering helps providers identify and communicate best practices for delivering better outcomes at lower costs.

Panel B compares the performance of three bariatric surgeons doing the two different procedures. For gastric bypass surgery, Surgeon B should learn why he incurs higher costs, but he could coach the two other surgeons on how to lower the incidence of revision surgeries, readmissions, and complications. For laparoscopic surgeries, we learn that all three surgeons incur comparable costs and deliver mostly comparable outcomes. Surgeon A has a higher readmission rate that should be addressed.

Panel C compares the outcomes and costs for three surgeons in the same orthopedic practice doing Total Knee and Total Hip Replacements. Dr. Jones has considerably lower costs than and comparable outcomes to the other two physicians. They could observe and learn from her about how to lower their total care cycle costs. Also, Drs. Hopper and Planck can improve their 30-day readmission rates and patients’ pain and physical health scores.

Multisite organizations, such as large hospital systems and the U.S. Veterans Administration, can implement Value-Based Health Care by measuring outcomes and costs for treating the same medical condition across all their facilities. They can use radar charts to display and compare outcomes and costs, enabling them to identify which facilities are in the top 10% on outcomes and efficiencies (e.g., low costs) and then to disseminate those facilities’ best practices to facilities currently below the median along those dimensions. Sharing best practices is the fastest and most powerful way to improve outcomes and costs across healthcare systems.

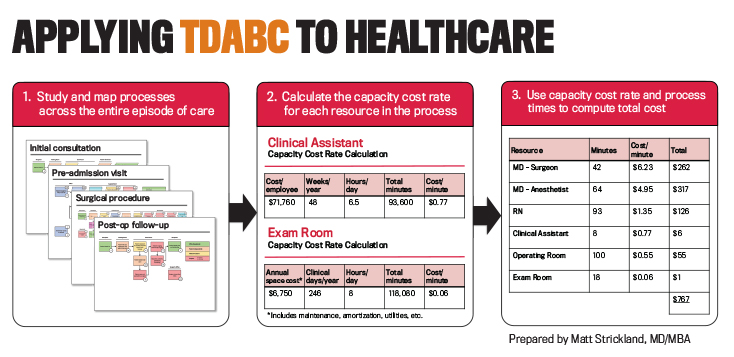

Time-driven activity-based costing enables providers to accurately measure the costs of treating patients for a specific medical condition across a full longitudinal care cycle. Unlike the top-down allocations that healthcare providers have traditionally used, TDABC is a bottom-up approach consisting of two steps: (1) mapping clinical and administrative processes and (2) estimating the capacity cost rates for personnel and equipment. Project team members start by identifying the high-level events in a care cycle, and then they drill down into the process steps that occur in each event (see Panel 1). They identify which personnel and equipment resources are used at each activity and the number of minutes used of each resource at the activity.

Parallel to the process mapping, the finance staff develops the cost component by constructing a dollar-per-minute capacity cost rate for each clinical resource involved in the care cycle. The numerator in the capacity cost rate is the total cost the provider organization incurs to make each resource productive and available for the patient. Personnel costs include compensation and the costs of office space, technology, training, supervision, and other indirect expenses incurred to support each staff person. Space and equipment costs include depreciation or rental expense and the costs of the space occupied, utilities, consumable supplies, and maintenance and repair. The denominator is the estimated total capacity, measured in hours or minutes during which each resource is available for productive work (see Panel 2). Personnel capacity is total clinical time available for work minus the time not available because of vacations, holidays, training, education, research, meetings, and breaks during the day. Space and equipment capacity is total budgeted time available during normal working hours minus maintenance and scheduled downtime.

The dollar-per-minute capacity cost rate is multiplied by the time spent by each resource involved in a process step to measure the cost of the clinical and staff resources used at each process step. For example, if a nurse spends 20 minutes with a patient during an office visit (includes prep and follow-up time) and the fully loaded cost for that nurse is $1.50 per minute, then the cost of nursing time for the visit is $30. The costs of any consumable supplies (medications, syringes, catheters, devices, implants, stents, etc.) used are added to this amount to obtain the total cost of performing the process step. The TDABC estimate of the total cost of caring for the patient is the sum of all the process step costs over the entire care cycle (see Panel 3). The project team incorporates risk adjustments and care variability by including decision nodes that depict alternative care paths to be followed when appropriate for a patient’s specific circumstances.

Often the project team focuses only on personnel and material costs, which comprise the majority of expenses incurred in the clinical units. In principle, the pilot sites have the ability to perform similar analyses—process maps and capacity cost rates of employees, equipment, and space—for ancillary departments, such as imaging, pathology, pharmacy, and central sterilization, and for the provider’s indirect and support departments, such as billing, collections, dietary, housekeeping, human resources, finance, and IT.

TO LEARN MORE

Here are some additional articles that help explain what’s going on in healthcare:

Michael E. Porter and Robert S. Kaplan, “How to Pay for Health Care,” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2016.

Michael E. Porter, Stefan Larsson, and Thomas H. Lee, “Standardizing Patient Outcomes Measurement,” The New England Journal of Medicine, February 10, 2016.

Derek A. Haas and Robert S. Kaplan, “Variation in the Cost of Care for Primary Total Knee Arthroplasties,” Arthroplasty Today, 2016.

Robert S. Kaplan and Derek A. Haas, “How Not to Cut Health Care Costs,” Harvard Business Review, November 2014.

Michael E. Porter and Thomas H. Lee,“The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care,”Harvard Business Review, October 2013.

Robert S. Kaplan and Michael E. Porter,“The Big Idea: How to Solve the Cost Crisis in Health Care," Harvard Business Review, September 2011.

January 2017