While I don’t claim to have all the answers to these questions, I have come up with some solutions that at least partially address these challenges. In-class Excel-based projects can both engage students at a deeper level of understanding and also help them develop the Excel skills they will need on the job. These projects are self-paced, active-learning assignments that students describe as some of the most memorable, enjoyable, and beneficial parts of the course.

My journey to create Excel-based active learning projects began about eight years ago. Like many instructors, I was trying to find innovative ways to engage students. In my introductory management accounting course at Case Western Reserve University, the vast majority of students are business students who don’t intend to become accounting majors. Thus, their motivation level tends to be lower than what we expect from, say, students in upper-level accounting courses. I knew I needed to do something to help these students understand how beneficial management accounting would be to their future careers and that it needed to be done in such a way that would allow them to be actively engaged in the learning process. I decided to take a stab at mimicking or simulating the information generation and decision-making activities they would someday encounter in their business careers by using the most prevalent technology in practice: Microsoft Excel.

To date, I have developed and class-tested seven Excel-based projects on core management accounting topics: job costing, process costing, cost behavior, cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis, budgeting, flexible budgeting, and division performance evaluation. I devote seven of my 28 class periods to working on these projects. Since they’re independent rather than serial in nature, instructors can pick and choose the ones that would be most useful and relevant for their students.

BENEFITS OF EXCEL-BASED PROJECTS

The projects are useful and beneficial from both a pedagogical and professional standpoint. From a pedagogical standpoint, they allow students to actively engage in the learning process rather than passively listen to a lecture. Since the projects are self-paced, high-achieving students can move through the projects more rapidly while those who need more time can move at a slower pace. Students appreciate working at their own pace rather than being held captive to an instructor-led pace. Educational theory, such as Dale Edgar’s Cone of Experience, suggests that learners remember a much higher percentage (about 70%-90%) of what they say and do (active learning) and a much lower percentage (about 10%-20%) of what they read and hear (passive learning). Simulating a real experience is second only to doing the real thing, placing these projects high on the active-learning scale.

In addition, these projects move students up from the basic “remembering” and “understanding” levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy to the “apply,” “analyze,” and “evaluate” levels. True, students in the introductory management accounting class are novices. But after covering the basics of the material, there’s no reason they can’t scale further up to higher levels of learning. Feedback from students has affirmed that the projects help solidify their understanding of the concepts that they first encountered in textbook readings, class, and homework assignments. These projects take students one step further by asking them to apply what they have learned to new situations, draw connections among ideas, and justify a stand or decision.

From a professional standpoint, the projects help students refine practical skills they’ll need on the job. Excel skills are in high demand for all business majors, not just accounting students. Part of my motivation for creating these projects was driven by comments received from employers: They wanted our students to possess Excel skills for both internships and full-time employment.

At the time I started developing these projects, our curriculum didn’t include a stand-alone Excel course, and these projects would help students become more comfortable working in Excel. Even now that Case Western has a required Excel course for accounting majors, it isn’t a prerequisite until the Intermediate Accounting sequence. Therefore, these projects serve as a “warm-up,” so to speak, getting students ready to learn the advanced Excel techniques they’ll encounter in the Excel course. In that course, our faculty can quickly breeze through the use of basic formulas and so forth since students have been exposed to these tools through the management accounting projects.

These projects can also help schools address accreditation standards related to technology. The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) Accreditation Standard A7 now requires that curricula “include learning experiences that develop skills…related to…effectively utilizing technology.” The standard further asserts that the development of technology-related skills shouldn’t take place in just one course but across the curriculum. These projects are a means of implementing this standard in the management accounting course.

These projects also fit well with the IMA Management Accounting Competency Framework. One of the five major categories in the Framework is technology, including “information systems and software literacy.” According to the Framework, management accountants should be able to “use technology to solve problems, analyze data, and enhance business performance.” It includes five levels of software literacy, ranging from limited knowledge to expert knowledge. These projects hone in on the mid-level skills:

- Basic knowledge: Manipulate spreadsheet data using simple arithmetic functions (formulas).

- Applied knowledge: Use spreadsheet functions (such as graphs) with ease.

- Skilled: Design organizational templates for use by others.

While most of the projects fall into the basic knowledge range, others delve into applied and skilled levels of knowledge with Excel graphing features and regression analysis and by requiring students to create templates that can be reused repeatedly by an organization simply by changing the underlying assumptions.

The projects fit well with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ Functional Core Competencies for the Accounting Profession. Most specifically, they address the “Leverage Technology to Develop and Enhance Functional Competencies” subcategory. Worth noting, the new CPA (Certified Public Accountant) exam features more task-based simulations and fewer multiple-choice questions. The Excel-based projects are, in essence, simulations of business scenarios that require management accounting analysis and insight.

Finally, the projects are consistent with the American Accounting Association’s Vision Model, which aspires to help students understand that the accounting profession is really about turning economic events into information useful for making decisions. Each of these projects begins with raw data and requires students to use management accounting analysis and critical thought to turn the data into decision-useful information.

OVERVIEW OF PROJECTS

Each of the seven projects addresses concepts that students likely will encounter in business situations in their careers. When they do, the students will be able to draw on their firsthand experience from these projects, applying what they learned about analyzing information with Excel to real-life situations. Here’s a brief description of each project, along with the student feedback collected during the spring 2017 semester (see “Student Feedback” for more reactions from this semester).

JOB COSTING

The objective of this project is to deepen students’ understanding of the job costing process using actual business documents. This project helps students go beyond the basic concepts by experiencing management decisions and the underlying process through which a job’s cost is determined.

The project begins with a customer order for several handbags. Students are guided through 21 requirements to ultimately find the gross profit on the sale to the customer. For example, students must find the optimal job size based on engineering efficiencies and stock requirements, estimate production time based on activity-time studies, schedule production based on the availability of plant capacity and skilled labor, determine the materials needed to be purchased based on materials already in stock, place purchase orders to several authorized suppliers, update the raw materials records upon receipt of the materials, requisition materials for the job, determine direct labor costs from labor time records, calculate and apply the overhead rate, and, finally, complete the job cost record.

After the job cost has been determined, students are required to critically analyze how the job cost would have differed had the allocation basis been different, had the company used LIFO (last-in, first-out) instead of FIFO (first-in, first-out) (one material had a price change), or had the equipment been older (fully depreciated). Students must brainstorm how the job could be produced less expensively in the future. They are also asked to reconsider the sales price based on a hypothetical competitor. Finally, students make the journal entries associated with the job, though this requirement can be easily removed without affecting the rest of the project.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience: 98.7% agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 95.2%

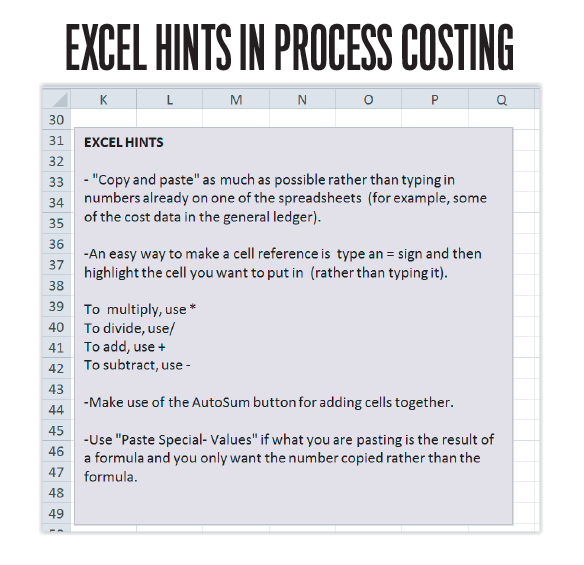

PROCESS COSTING

This project is intended to extend students’ understanding of how process costing is used to determine the product cost of one unit and how, in turn, the product cost impacts the company’s financial statements. Students receive an outline of a production cost report, journal entries for the period, and a client scenario. From this information, they create a reusable production cost report template to find the unit cost. Then, given additional information, they find the balance in work-in-process inventory and finished goods inventory and create the company’s income statement. Finally, they analyze how a different percentage of completion assumption would affect these financial statement figures.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience: 92.3% agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 97.1%

COST BEHAVIOR

The objective is for students to learn how to analyze cost behavior through regression analysis and scatterplots. Given historical data about two potential cost drivers and the company’s operating costs, students are required to create scatterplots of the data, identify potential outliers, run regression analysis, interpret the r-squared statistic, compare the results of the regression analysis to the high-low method, and make cost predictions based on both methods. Finally, they’re asked to determine which of the potential cost drivers management should use to make cost predictions in the future, providing support for their choice.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience: 97.2% agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 99.0%

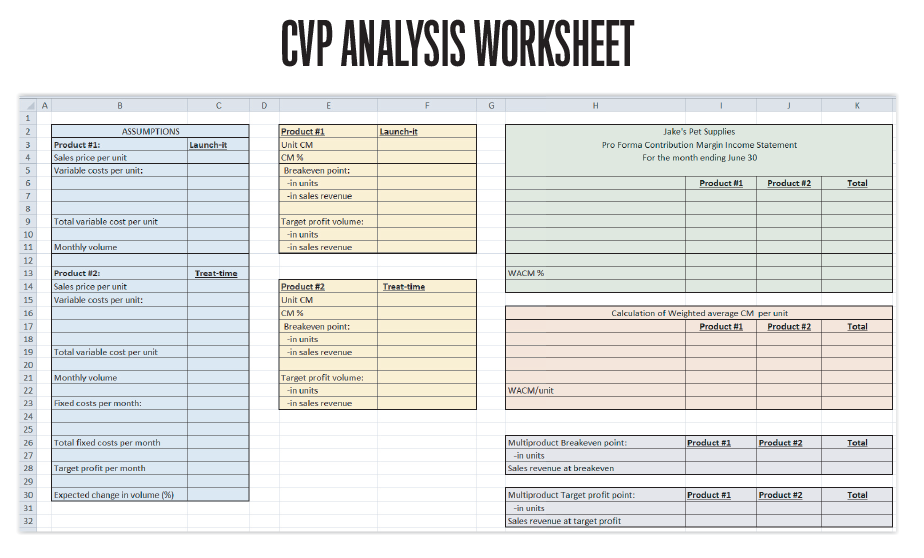

CVP ANALYSIS

In this project, the objective is to strengthen students’ understanding of the CVP relationships by creating a reusable CVP model for the entrepreneur of a two-product firm. Students are given background information about a start-up business and asked to formulate a model that includes the breakeven point, target profit point, pro forma income statement, weighted average contribution margin percentage, margin of safety, and operating leverage factor. Once the model has been created, students use it to answer questions about changing business conditions (supplier cost increase, potentially different salary and commission structure for employees, product sales mix) and explain to the client what these changes would mean for the business’s expected financial performance.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience: 92.4% agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 72.4% (Note: This was the first semester class-testing this project, so there were a few project details that I amended after receiving student feedback.)

PERSONAL BUDGET

While business budgeting may be the perfect topic for building Excel skills, this project moves students beyond the number-crunching aspect of budgeting and into the process of researching and estimating costs, making allocation decisions, making cost containment decisions, and gaining an awareness of how much impact location can have on costs, revenues, and taxation.

Students are provided with a direction packet and a budget template that contains 65 separate line items categorized into housing, transportation, insurance, entertainment, food, taxes, savings, and so forth. The line items are provided since most traditional students don’t realize how many types of cash outflows they will be responsible for in adult life. In this project, students first decide where they want to live immediately following graduation from college and then research starting salaries for their chosen career, apartment costs, and so forth for that location. They are also required to calculate FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act), federal, state, and local income taxes using provided instructions and web links. The federal tax calculation is a very modified IRS Form 1040, containing only those items that I would expect most recent college graduates to have.

Once students have created their first budget, they implement at least five realistic cost-cutting initiatives to arrive at an amended budget. The project concludes with a written reflection in which students elaborate on their cost-cutting initiatives, describe what they have learned, and compare and contrast business and personal budgeting.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience: 88.6% agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 90.5%

This project elicits extremely positive student comments. Most students are truly appreciative of the lessons they learned while completing it.

DIVISION PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

The objective is to develop students’ understanding of how to locate descriptive and financial information about a company’s reportable operating segments in a 10K, in accordance with Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 131, and use it to evaluate and compare the financial performance of each segment.

Students are given a brief overview of the structure of a 10K. Then, after reading about a selected business, they’re asked to find the appropriate footnote disclosure containing information on the company’s operating segments. Starting with a blank Excel spreadsheet, students create tables and graphs containing relevant financial data, then calculate the return on investment (ROI) as well as other financial performance metrics. They must critically assess how segment managers could improve performance on each of the metrics and are required to make a capital allocation decision and provide supporting rationale.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience? 85.7% strongly agree or tend to agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 92.4%

FLEXIBLE BUDGETING

This project aims to deepen students’ understanding of how a flexible budget can be used to help management isolate and assess variances due to volume and other factors. After being given budget assumptions and actual results for the period, students are required to create a planning budget, calculate variances, and assess whether they are favorable or unfavorable using “if-then” statements. Next, they create a flexible budget performance report to isolate the volume variance and flexible budget variance and brainstorm possible causes of the variances. Finally, students are given management’s assertions about business operations and are required to determine whether the variances for each line item are consistent, unexplained, or inconsistent with management’s story.

Student feedback: Valuable learning experience? 91.4% strongly agree or tend to agree Keep using in future semesters? Yes = 97.1%

USING THE PROJECTS

There are many different options for using these projects as part of a course. They can be worked on in class or outside of class. They can be paired with an associated lecture or not. They can be used as a learning activity or to assess student understanding. They can be presented in a computer lab, or students can use their individual laptops. Students can be asked to work on them alone or paired with partners or a group. And so on. Since there is quite a bit of flexibility, I’ll stick with describing how I use them.

First and foremost, I developed these projects as a means to actively engage students in class. One of the side benefits of having students complete the projects in class is that there’s little to no risk of plagiarism. In one semester, I assigned the cost behavior project as an assignment outside of class in order to save class time. Unfortunately, when I was grading the projects, I recognized the same grammatically incorrect sentence in two projects, leading me to find that two projects were identical. One student had simply copied the other student’s file and submitted it as his own. By having students complete the projects in class, I avoid this risk because I can see students actively working on the projects right in front of me. Most of the projects can be completed within a 75-minute class period. If students need longer, they can finish it outside of class, but I really don’t worry about plagiarism at that point since most have completed the bulk of the project by the time they leave class.

I have students work with a partner on all projects except for the personal budget project. Working in pairs gives them some level of comfort, allowing them to discuss and share their thoughts about both the management accounting content and the Excel operations. Most of my students have very limited experience with Excel before taking the class. Even though the projects contain directions for basic Excel operations, I find that the students help each other learn more about Excel—including some of its time-saving shortcuts—simply by working together.

Some pairs prefer to work together on one Excel spreadsheet, making it truly a joint project, while other pairs decide to work on their own spreadsheets to get more practice but consult each other when questions arise. I let students use either approach to complete the projects. In the end, each partnership submits only one project for grading. Each partner receives the same grade unless one of the partners feels that the other partner didn’t contribute equally.

I primarily view these projects as learning activities that will deepen students’ understanding of the material, not as assessments of their current state of knowledge. I do grade the projects to make sure students take them seriously, but I only place about a 2% grade weight on each project.

Since I view the projects as learning activities, I walk around the classroom and help students if they have questions. Even if they don’t, I’ll draw their attention to anything I notice that might be wrong so that they can reexamine it and get back on track. Several of the projects also include check figures so that students can self-assess whether they have done everything properly up to the checkpoint. As a result of these interventions, the projects are usually in very good shape when they’re submitted, making the grading relatively simple.

I have students bring their own laptops to our classroom on project days since our building doesn’t have a dedicated computer classroom. One benefit of having students use their own laptops is that they don’t have to learn a potentially different computer operating system (like Mac or PC) from what they are used to. While I ask them all to download the most recent version of Excel, it isn’t unusual to have students with different Excel versions loaded on their laptops, including Chinese and Arabic Excel. The projects use relatively basic Excel features, so the version of Excel doesn’t seem to matter. (But having Excel does matter. One pair of students ran into problems when they attempted to use Google Sheets rather than Microsoft Excel.) And because of standardized icons and toolbar formats, I’ve still been able to help international students using non-English versions of Excel.

Finally, these projects can work in either a flipped or traditional classroom setting. For some of the projects, I lecture on the topics before having students complete the associated projects. Students must always complete an assigned reading from the textbook before we do the project. To supplement the reading, the course textbook’s online homework package comes with short lecture videos that students can watch if they would also like to have the material explained to them.

CONCEPTS IN ACTION

The projects are available for any professor who would like to use them. They’ve been designed and created in a way that you can also edit or amend them as you see fit. The projects are housed at a nonsearchable Google website for convenience: https://sites.google.com/case.edu/excel-for-management-acctg/home. Professors should contact me directly for the suggested solutions.

These projects simulate business conditions that students may one day find themselves facing. Students will benefit from having a deeply rooted understanding of these topics, including how the underlying accounting information was generated as well as the assumptions, methods, choices, and judgment that influenced its outcome. By starting with raw data and turning it into decision-useful information, students deepen their knowledge and understanding of management accounting while simultaneously building Excel skills that will be critical to their success as finance-function professionals.

STUDENT FEEDBACK

As a whole student feedback on the projects has been overwhelmingly positive. For each project, I ask students to rate the statement, “The [project name] was a valuable learning experience,” on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

I also ask students to answer “yes” or “no” to the statement “Should I keep using [project name] in future semesters?” In the spring 2017 semester (n = 108; 99% response rate), 85.7%-98.7% of students agreed that “the project was a valuable learning experience,” and 72.4%- 99% of students said that I should keep using the projects in future semesters. These results are similar to previous semesters. The only project that was rated below 90% in the spring 2017 semester was the CVP (cost-volume-profit) project, which was being class-tested for the first time. I subsequently modified the project based on the student feedback.

In addition to the specific questions about each project, I also give students the opportunity to provide open-ended comments for each project. A substantial percentage of students always list the projects among the most memorable and impactful aspects of the course. Here are a few representative student comments about the projects:

- The projects we do in class really helped me a lot since they were all real business examples, and it just helped me understand the material a lot better.

- The biggest takeaway from Acct 102 was the projects because they required the application of knowledge.

- The projects that we did in class were very helpful for application of accounting in real-world scenarios.

- I really liked the in-class projects and felt they furthered my understanding of the subject we were learning in class.

- I will remember the projects the most. They were very applicable and easy to understand. They helped me understand the topics we covered and made it easy to see the real-life application.

- It was like we were really doing it in real life.

- Helped me learn Excel.

- Real hands-on experience.

- The projects we did in class were fun to do, and I learned a lot.

August 2017