Many large companies, such as Lands’ End, Bank of America, Disney, Hallmark, Universal Studios, Scooter Store, and the Container Store, have tried to address this problem by hiring motivational consultants to help find ways to praise, encourage, and commend entitled employees to keep them happy and productive. Our own research on psychological entitlement leads us to believe that understanding what psychological entitlement is and how it affects individuals’ motivations and behaviors can provide more nuanced and effective techniques for managing entitled employees—rather than simply doling out rewards and praise at every opportunity.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ENTITLEMENT

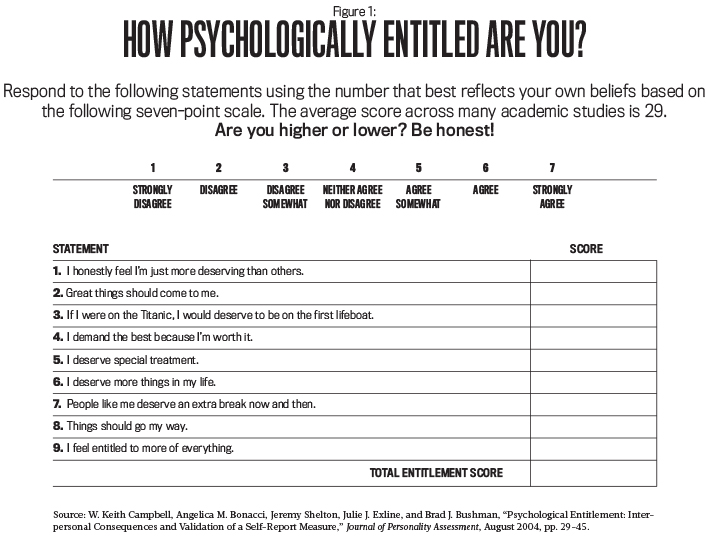

Psychological entitlement is a personality trait defined as a stable and pervasive sense of deservingness—in other words, the sense that one has a right or claim to rewards, assistance, attention, or special treatment. (It’s important to note that this trait can vary from very low levels to very high levels. For simplicity, we refer to individuals on the higher end of the spectrum as entitled. Those on the lower end are described as not entitled.) Entitled individuals feel a strong sense of superiority to others, particularly peers, which leads to high expectations of reward and preferential treatment regardless of their ability or performance. Does this sound like someone you know (maybe even you)? Complete the Psychological Entitlement Scale in Figure 1 to find out how psychologically entitled you are. And be honest!

Entitled individuals’ sense of deservingness stems from who they are, not what they do. This creates significant problems for managers dealing with entitled employees. In fact, research has found that psychological entitlement is associated with undesirable workplace outcomes such as unethical behavior, corruption, conflict with supervisors, perceived compensation inequities, low levels of job satisfaction, and high levels of turnover. Entitled individuals have also been described by academics and the business press as being resistant to feedback, inclined to overestimate their talents and accomplishments, and likely to blame others for mistakes.

Psychological entitlement isn’t a new concept, but its relevance is on the rise. Though entitled individuals can be found in every generation, the average Millennial is reported to be more entitled than those in previous generations. (For more information, see Generation Me by psychology professor Jean Twenge, among other sources.) Consequently, the prevalence of entitlement in the workplace is likely to increase as Millennials become a larger part of the labor force.

Although research into the causes of entitlement is limited, experts point to increases in psychological entitlement coming from social and parenting causes embodied by concepts such as “no child left behind,” “every kid gets a trophy,” and “helicopter parenting” that typify the upbringing of the Millennial generation. If entitlement is a function of parenting, it’s unlikely that a couple of years in the workplace will eradicate psychological entitlement.

So what are managers to do? The knee-jerk reaction may be to avoid hiring anyone under 30. But we think there’s a more practical approach, and it’s grounded in gaining a better understanding of what makes entitled employees tick.

The first thing to understand about entitled individuals is that they a have unique way of interacting and communicating with others, including managers. On the one hand, they have a strong desire for autonomy. Psychologically entitled individuals dislike the idea of being beholden to others or being told what to do. On the other hand, they also exhibit a strong preference for what is known as sociotropy, meaning that they place a high value on the approval and affection of others. These dual—and somewhat conflicting—preferences for interaction and communication create a significant challenge for managers dealing with entitled employees.

Understanding these desires creates an opportunity for managers to design incentives and controls to manage entitled employees more effectively. We conducted two research studies to examine management techniques for dealing with entitled employees. The first looked at improving their performance through feedback. The second examined improving performance through monitoring.

PROVIDING FEEDBACK

Feedback is essential to improving employee performance. Managers can deliver positive feedback (e.g., “Your production this month was above average”) or negative feedback (e.g., “Your sales this month didn’t meet your forecast”). While it would certainly be nice if managers could exclusively provide positive feedback, there are times when managers have to tell employees that they are underperforming and how they can improve.

Our first study examined how best to provide negative feedback to entitled employees, who have hard-wired expectations of praise. To do so, we had participants complete a task wherein they decoded number sequences. After one round of completing the experimental task, we provided various forms of feedback and then measured how performance improved during a second round of the same task. We examined whether entitled individuals responded better to positive or negative performance feedback as well as whether entitled individuals responded better to receiving the feedback from a peer or a supervisor.

Our results show that everyone—entitled or not—welcomes positive feedback regardless of whether it comes from a peer or a supervisor. What’s more, positive feedback leads to a slight improvement in performance.

The results also show, however, that negative feedback is more effective at improving performance than positive feedback, but it needs to come from the right source. Entitled individuals displayed higher performance increases when receiving negative feedback from a supervisor than when receiving negative feedback from a peer. The reverse was true for individuals who aren’t entitled. Those individuals benefitted more from negative feedback that came from a peer rather than from a supervisor.

Why does it matter who delivers negative feedback to entitled employees? Entitled individuals are very sensitive to how they are viewed by others. They think highly of themselves, and they’re eager to prove to their supervisors that they are as deserving as they claim. But because entitled individuals have a tendency to believe they are superior to their peers, they don’t appear to be as concerned about their peers’ opinions.

PROPER MONITORING

The inflated sense of deservingness in entitled employees can lead to negative workplace behavior. For example, if entitled employees are awarded a 10% sales commission but feel they deserve a 15% commission, they may respond to the perceived injustice by not working as hard or, in more extreme cases, by misappropriating assets from the company. Our second study examined a way to increase performance and discourage deviant behavior by using a type of performance monitoring tailored to the interpersonal styles of the entitled.

We gave each participant a packet of paper-based mazes and asked everyone to complete as many as they could in order. Participants then reported how many mazes they completed successfully and placed their packets in a common bin. Half of our participants worked without any form of monitoring, while the other half were told that their work would be verified at a later date.

Participants were paid based on how many mazes they reported having completed. The packets had no visible identifiers, so participants would believe that any overreporting would go undetected. But we marked each packet in invisible ink, which enabled us to later manually grade the mazes and compare actual performance with reported performance. Thus we were able to determine the extent to which participants overreported their performance.

In the absence of any monitoring, entitled individuals put forth lower effort and misreported their performance more than individuals who aren’t entitled. This is consistent with the notion that psychologically entitled individuals feel they deserve rewards regardless of performance. It also suggests that entitled individuals are more likely to engage in questionable behavior to get what they believe they deserve.

For those participants who were monitored, we used a form of monitoring that capitalized on entitled individuals’ desire for autonomy and the approval of others. Specifically, we devised a system of future accountability. We allowed participants to work independently, but we advised them that their work would be reviewed at a later date. Under this system, entitled individuals put forth more effort and misreported less than individuals who aren’t entitled. Why? Entitled individuals really care about how they are viewed by others.

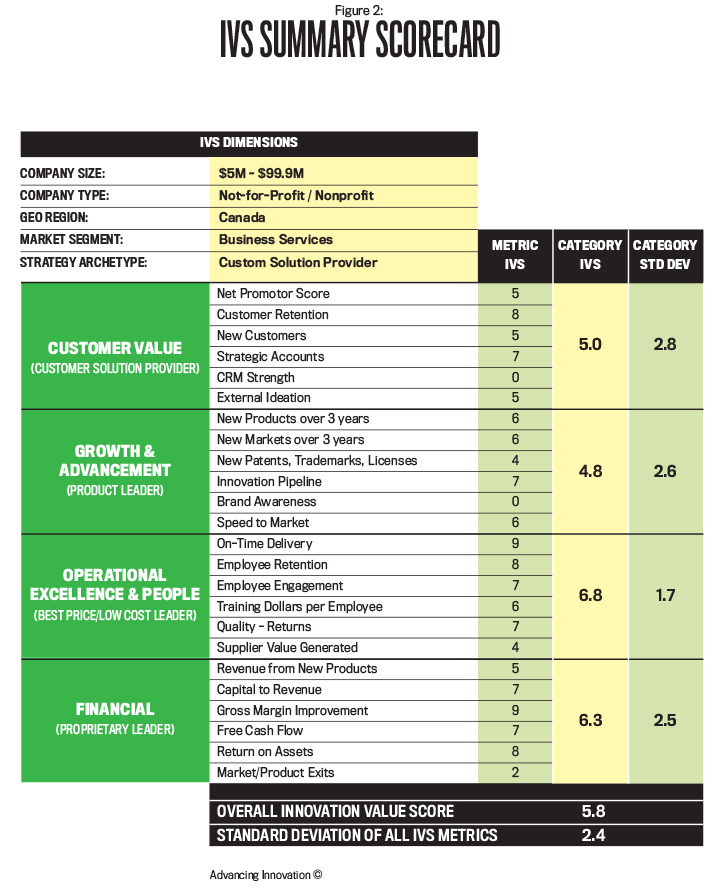

We learn from this study that entitled individuals use the assurance of future verification as an opportunity to influence the opinion of a supervisor (see Figure 2). The desire to be viewed favorably appears to mitigate entitled individuals’ propensity to take unethical shortcuts to receive the rewards they feel they deserve.

TAKEAWAYS FOR MANAGERS

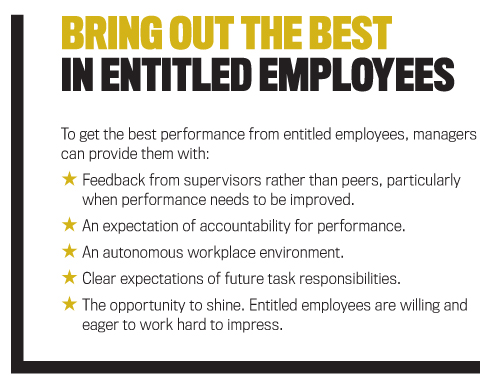

Our studies point to several key takeaways that can be useful for managers dealing with entitled employees. First, ensure that communications about an entitled individual’s performance come from someone in a position of authority, especially when delivering negative performance feedback. Negative feedback is typically a critical way to provide constructive ideas for improvement and to motivate employees to work hard. Managers don’t need to shy away from giving psychologically entitled individuals negative feedback, but they should be aware that such feedback is more effective when delivered by an authority figure.

Second, establish clear expectations about task responsibilities, but allow individuals the freedom to complete the tasks as they see fit. Psychologically entitled individuals don’t want to be told what to do step by step. They perform better when allowed to work on their own and feel ownership over their efforts. Remember that entitled individuals care about what others think of them, so they will take advantage of opportunities to demonstrate their worth to an organization. Managers should establish clear rules and responsibilities up front about what work outcomes are needed but then allow individuals to complete tasks in the manner they see fit.

Third, establish clear expectations about when and how performance evaluations will take place, but allow sufficient time between performance feedback episodes for employees to feel autonomous in their work. If supervisory communications or performance feedback are too frequent, psychologically entitled individuals are likely to become agitated and bothered. Managers should give entitled employees more space and independence in their work.

This isn’t to say managers can’t have high standards and expectations; rather, we highlight that monitoring at a distance can be beneficial. Psychologically entitled individuals want their managers to hold them in high regard, but they also don’t want to feel like managers are constantly watching over their shoulder.

BE AWARE OF PERSONALITIES

To implement these techniques successfully, managers must gain an awareness of their employees’ personalities. Some firms conduct personality assessments of employees as part of the process of hiring new employees. These assessments have become more common with recent technological advancements rendering them less costly and more accurate. In fact, The Wall Street Journal notes a significant increase in the use of pre-hiring personality assessments from 26% of large U.S. employers in 2001 to 57% as of 2013 (Lauren Weber, “Today’s Personality Tests Raise the Bar for Job Seekers,” April 14, 2015).

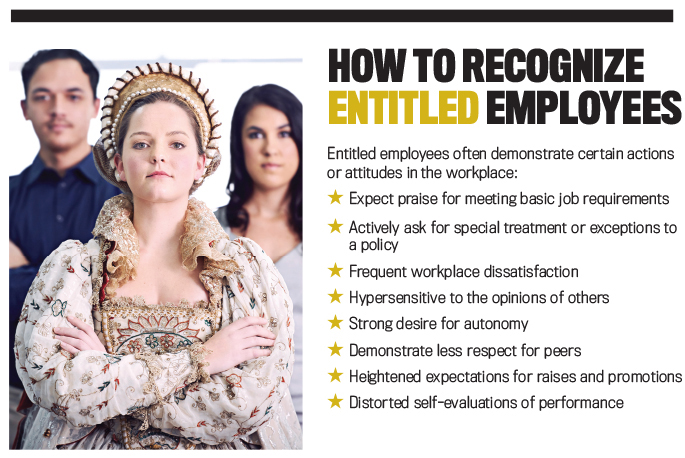

When such screening procedures aren’t feasible, managers are often able to assess personality traits of employees through personal interactions and observations. Research in psychology has found that individuals are pretty good at making accurate assessments of others’ personalities. For example, managers can notice entitled employees from behaviors such as expecting praise for meeting basic job requirements, actively asking for special treatment or exceptions to policies, or frequently showing dissatisfaction with company policies or reward systems.

Once the personalities are assessed, managers can base their feedback and monitoring accordingly. It may not always be feasible to tailor management approaches to specific individuals, but if a given group of employees is known to display greater feelings of entitlement, then workplace tasks and associated management approaches could be established for the group as whole. For example, companies are increasingly providing work-at-home or telecommuting options or basing compensation on more outcome-based performance measures. These more autonomous work arrangements may be beneficial when managing entitled employees.

Just because an employee might be psychologically entitled doesn’t mean he or she is a bad member of the team. It would be impractical to avoid hiring entitled employees, and it could cost you valuable contributors to the team. As with any other management situation that involves supervising and leading employees, having an informed understanding of the issue and being prepared to address it effectively can create better results. In this instance, it’s important for managers to be aware of how psychological entitlement affects an individual’s behavior in the workplace. Providing the proper feedback and performance monitoring can help manage these employees more effectively and realize greater performance from them.

This article is based on a study funded by the IMA® Research Foundation.

October 2016