That creates a challenge. Conventional accounting draws only a partial picture of a business’s true condition and ability to create value. Although nonfinancial resources such as human, social, and natural capital are critical sources of future value, conventional accounting doesn’t treat them as assets. It doesn’t account for their value at all.

To address this gap, for many years investors have sought information about nonfinancial issues, and companies have, to varying degrees and in varying forms, provided it. One popular format is the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report. Instead of—or in addition to—the CSR, some companies may discuss these nonfinancial factors on their websites or in responses to specific questions from investor surveys. Others may provide some information about these factors in their 10-K or 20-F filings with the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) or choose yet another communication method.

Still, the connection between companies’ tangible assets—those that conventional accounting can measure reliably—and their market value has weakened. In 1975, tangible assets made up more than 80% of the Standard & Poor’s 500 market value, and intangible assets made up less than 20%. By last year, those numbers had reversed, a trend that’s unlikely to change direction. As the industries shaping our economy—such as the Internet, media & services, and biotech—increasingly rely on human capital, technology, and innovation, intangible assets will play a growing role in their success.

Even though companies are disclosing more information, this information often isn’t what investors need to make decisions. Without accounting metrics to measure nonfinancial resources and their management, investors struggle to understand the sustainability impacts on companies, and companies themselves may struggle to measure and manage critical issues, a situation that could threaten their viability. No business is likely to thrive long term if its leaders are able to influence only 20% of what generates value.

IT'S ABOUT QUALITY, NOT QUANTITY

It’s time for a different approach, one that gives both investors and management a more transparent, more complete view of all the factors that affect business outcomes.

Sustainability accounting can help complete the picture that conventional accounting has begun. It can extend accounting structure to capture the sustainability factors that are likely to have material impacts on a company. For example, the ability to source cotton, a crop that’s vulnerable to shifting weather patterns, is important for apparel companies. The energy intensity of data centers is important to software and IT companies. The number of recalls because of safety violations is important to automobile companies. In the process, sustainability accounting can give investors and managers a method for better understanding and evaluating the sustainability factors that are vital to long-term prosperity.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) develops and maintains sustainability accounting standards for individual industries. Our goal is to improve the effectiveness of disclosure to investors by focusing on sustainability topics that affect the financial condition or operating performance of a company. Because they’re linked directly to financial impacts, these same sustainability topics can also play a critical role in business strategy and management, a fact that many corporate leaders recognize.

A 2011 McKinsey survey, “The business of sustainability: McKinsey Global Survey results,” found that 76% of CEOs believe strong sustainability performance will contribute positively to the long-term health of the business. And a 2013 Accenture survey, “The UN global compact—Accenture CEO study on sustainability,” found that 80% of CEOs believe their companies are leveraging sustainability to strengthen competitive advantage.

Evidence also shows that strong sustainability performance can improve a company’s returns—as long as that performance relates to the right issues. In a March 2015 working paper, “Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence of Materiality,” Harvard Business School professors Mozaffar Khan, George Serafeim, and Aaron Yoon reported that the risk-adjusted stock returns of firms with good ratings on material sustainability issues significantly surpass those of firms with good ratings on immaterial sustainability issues and those of firms with poor performance on either type of issue. The paper also found the same effect on return on sales, sales growth, return on assets, and return on equity. Using historical data, the study tracked the performance of 2,307 unique firms over 13,397 unique firm-years across six sectors and 45 industries and discovered that firms enjoyed significantly higher accounting and market returns when they addressed material sustainability factors and significantly higher returns still when they efficiently concentrated on material sustainability factors to the exclusion of immaterial sustainability factors. (See http://hbs.me/22mbGw0.)

MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS' ROLE

These trends illustrate the connection between sustainability accounting and the work of management accountants, who have long helped lead their organizations in the ongoing quest to understand and measure what creates value, whether those factors are explicitly financial or not.

Indeed, some of the companies that have led the development and implementation of management accounting practices recognized—and acted on—the link between sustainability and business results long before sustainability entered the mainstream business conversation. Lever Brothers, part of what is now Unilever, took a keen interest in employee welfare. In 1888, the company built the model village Port Sunlight in Wirral, Merseyside, England (on the banks of the River Mersey opposite Liverpool), to give employees who were manufacturing its soap comfortable, safe housing and access to community activities. It also provided pensions for elderly employees, and William Lever advocated for the state to introduce a national old-age pension.

Today, Unilever continues to act on the belief that managing ESG issues can improve outcomes. The goals of its Sustainable Living Plan, introduced in 2010, are to double the size of its business while reducing its environmental footprint and increasing its positive social impact.

Managing material sustainability factors can help all businesses withstand increasing public scrutiny and prepare for a future in which the prices of many resources may increase dramatically. But doing so can be a complex task, and sustainability accounting helps simplify it. It offers management accountants a powerful method to more fully understand key nonfinancial value drivers and to measure them in a cost-effective way.

SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING SHORTCOMINGS

At a glance, the sustainability reporting landscape can appear crowded and overwhelming. The wide variety of reporting forms has helped increase disclosure, but it also creates problems. Responding to multiple requests for sustainability information, which come from investors, ratings groups, or other entities, may consume substantial amounts of time without providing commensurate value to a company.

All these requests coming from investors, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and ratings agencies create a reporting burden for companies. On a recent IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) webinar poll, 7.5% of members attending said that they respond to more than 250 ESG requests or questionnaires per year. In 2014, GE reported that it developed responses to more than 650 requests from ratings groups alone. The company says the process took several months and involved more than 75 people across the organization with little benefit to GE and its shareholders. This scenario isn’t uncommon and results in part from the fact that most questionnaires and surveys fail to focus on the issues that matter to investors.

In addition, many frameworks for CSR reports cover a large number of broadly defined sustainability issues rather than focusing on the small handful of industry-specific impacts that are critical to value creation. This happens because these frameworks are designed to address all of the topics that may be considered material by a variety of different stakeholders, including employees, customers, vendors, and NGOs. Because their definition of materiality is inconsistent with that of the U.S. Supreme Court—which focuses solely on investors and governs SEC disclosure requirements—reports based on these frameworks can create confusion for investors and increased risk of securities litigation for companies.

The SEC also acknowledges the need to improve the quality of sustainability disclosure to investors. In April, it issued a concept release on disclosure reform, “Business and Financial Disclosure Required by Regulation S-K,” which includes 11 pages of discussion about sustainability disclosure and eight questions on which the SEC seeks input during a 90-day public comment period. This presents an historic opportunity for capital market participants to write to the SEC and express the need for sustainability accounting standards in order to make sustainability disclosure more cost effective for companies and useful to investors for making decisions.

THE SASB DIFFERENCE

Given these issues, it’s important to understand how sustainability reporting and sustainability accounting differ. For any company, the total amount of sustainability information of interest to stakeholders, both internal and external, is potentially vast. A subset of that information is genuinely relevant, and, with sustainability reporting, the CSR report, website, or other forum may be the ideal place to publish it. Sustainability accounting, on the other hand, takes investors as its audience and zooms in on just those factors that are likely to affect the financial condition or operating performance of a company. That is, it focuses on information that’s likely to be material. This is the information that belongs in statutory filings.

When it comes to sustainability, one size does not fit all. Sustainability issues affect different industries in different ways. Even issues that affect all industries do so through various mechanisms. Take climate change, for example. In the software and IT services industry, the energy intensity of data centers is a relevant metric. In banking, the emissions financed by financial institutions—i.e., loans to oil and gas, industrials, and utilities companies—matter far more than the emissions their branch networks release. In healthcare delivery, climate change creates the need to be prepared for major weather events and the migration of diseases.

In other cases, sustainability issues affect only some industries. Employee diversity, for instance, can affect media companies substantially. Without it, the businesses may fail to produce the books, movies, television programs, or newscasts that resonate with readers and watchers. And media consumers may then make different choices about how to spend their money and attention. Other industries, such as solar panel manufacturers, are less likely to be affected in a material way by employee diversity. For those firms, managing hazardous waste is often a key sustainability issue, one that has no material impact on media companies.

These differences make industry-specific metrics essential. Asking a software company, a bank, and a hospital to report the same climate-change-related data would fail to provide investors the information they need to evaluate those companies on that dimension. It might also encourage management to focus on activities that would have little impact on business value. Asking a media company to report on its hazardous waste management would be neither cost effective nor relevant.

Industry-specific metrics help businesses efficiently devote resources to managing risks. Managers at a bank, for example, may realize that shrinking loans to the coal industry is a far more efficient way to reduce climate change risk than initiating an energy-saving program for its offices. Of course, saving energy is a worthy goal, but changing its financing practices offers the bank more risk-reduction value for the money it spends. Based on data collected to report employee diversity, the leaders of a media company may see the true nature of the risk they face and, as a result, take action to reduce it. After working to assemble and report information on its hazardous-waste management practices, a solar panel manufacturer may uncover new layers of risk it needs to address.

MORE THAN JUST RISK MANAGEMENT

The value of assessing material sustainability information reaches beyond risk management. Companies can also discover opportunities for innovation to create competitive advantage. For example, two SASB metrics for the consumer finance industry cover financial inclusion. Specifically, they ask companies about revenues from credit and debit products targeting unbanked and underbanked segments and about the percentage of new accounts held by first-time credit card holders. When managers see their bank’s performance on this issue quantified, they may recognize potential for new products that could serve customers’ needs for alternative banking services and the bank’s need to capture market share, revenues, and assets.

Industry-specific KPIs also offer the advantage of comparability. Both investors and managers can see more clearly how any given company compares to others affected by similar sustainability issues.

Comparability also can spark innovation. For example, one of the SASB metrics for automakers covers fuel economy. It asks automakers to disclose sales-weighted-average passenger fleet fuel economy, consumption, or emissions by region. Managers comparing their company’s data to a competitor’s data may see they need to increase funding for research and development devoted to improving fuel economy or risk losing market share. Or they may notice a nascent trend toward high-efficiency vehicles in a part of the world where they’re planning to expand. In either case, the information can provide key input to the company’s strategy. It would be difficult, at best, for an automaker to derive this kind of benefit from sustainability metrics that ask for the same information from banks, media companies, and hospitals.

In turn, innovation can help strengthen a company’s reputation, which is often a substantial intangible asset. Sustainability accounting gives managers applicable metrics for those issues that are likely to be material, thereby helping companies accomplish two key tasks. First, sustainability accounting helps managers and management accountants influence the sustainability issues that matter to both the company’s performance and its reputation. Second, sustainability accounting helps both these groups communicate internally and externally about meaningful topics in a consistent, comprehensible way. Accounting is often called the “language of business,” and sustainability accounting adds to the lexicon of conventional accounting by identifying and defining key terms.

HOW WE DO IT

At SASB, we haven’t identified all the sustainability issues that will affect every company. Rather, we’ve set for ourselves the goal of identifying the minimum set of cost-effective disclosure topics that are likely to constitute material information for firms in an industry. Ultimately, companies are responsible for determining what’s material to them, and some may identify sustainability issues not covered by SASB standards but that are nonetheless material to them. In either case, SASB’s work offers a model for assessing potentially material issues.

When developing standards, we follow a rigorous process rooted in evidence and shaped by consensus. Our extensive research identifies topics for consideration based on evidence of financial impact and evidence of interest to a reasonable investor. We look for evidence in SEC filings; industry and academic research reports; legal news and litigation reports; environmental, social, and governance data; sell-side research and investor call transcripts; and government statistics and reports. As we examine the evidence, we ask ourselves such questions as:

- If a company improved performance on this issue, would that add value to the bottom line?

- Is regulation related to this issue pending or possible?

- Is this topic attracting media attention, specifically with respect to the industry in question?

- Are industry peers disclosing information related to this topic?

- Are shareholders asking about this topic?

These are the same kinds of questions management accountants and managers regularly consider in the context of conventional accounting because they relate so closely to performance management and strategy. Business leaders can now leverage SASB’s work to extend this rigorous thinking to the factors that conventional accounting often overlooks.

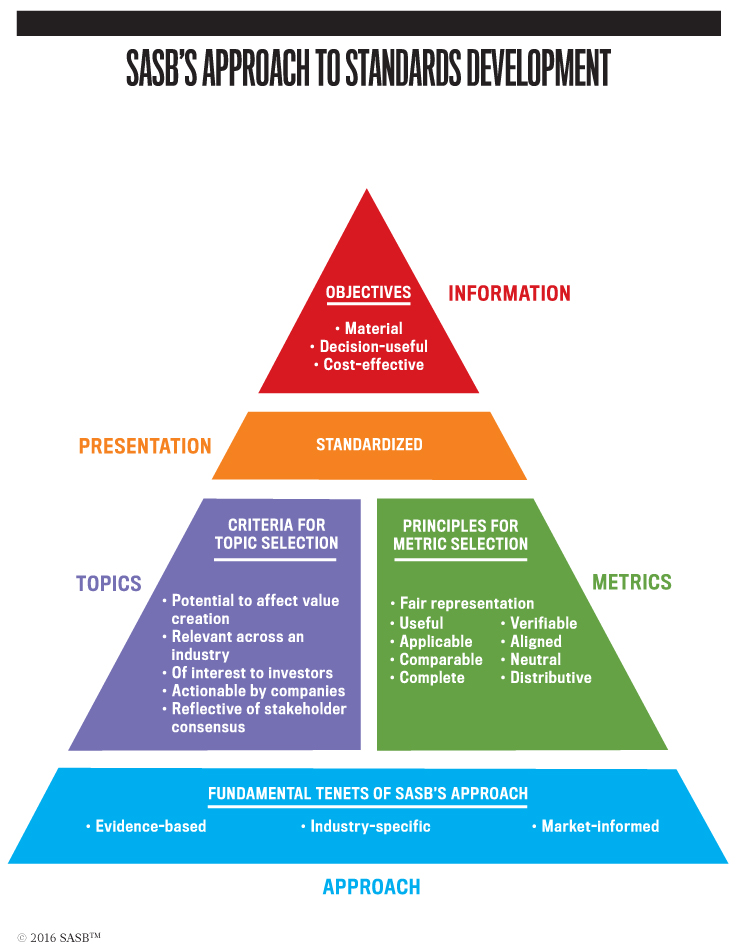

Throughout the standards-setting process, we solicit feedback from a group of industry experts—carefully balanced between issuers and investors—and the public, and we subject our work to independent oversight. Once standards are published, we have a long-term plan to review them so that our work keeps up with the need that helped inspire it: Business is always evolving. (See Figure 1 for an overview of the standards-setting process.)

HELP US HELP YOU

In March, SASB issued provisional standards for the last of its 10 sectors and 79 industries. Now, as we pivot toward standards codification and maintenance, we’re beginning a phase of deep consultation with issuers and investors to enhance the credibility of our process, the quality of our outcomes, and the transparency of our activities.

SASB has organized its standards-setting team around sector analysts to facilitate more productive, ongoing dialogue with stakeholders. Corporate issuers, in particular, can help us achieve these goals by engaging with our analysts about the relevance of the standards and the feasibility and cost effectiveness of their implementation. One way to do this is for companies to review the standards for their industry or industries and either consider or begin their implementation.

We provide a variety of tools and resources to help them get started.

Each SASB standard is accompanied by an industry research brief that provides an overview of the sustainability topics for which we’ve developed standards. These briefs describe in detail the channels through which those topics may impact a company’s financial condition or results of operations. Thus management accountants who spend an hour or two reading the brief applicable to their company will gain information to begin a meaningful discussion of both strategy and performance. They’ll also gain background and context for implementing SASB standards.

For further information about implementation, management accountants can consult SASB’s “Implementation Guide for Companies” and “Mock 10-Ks” (www.sasb.org). The Mock 10-Ks provide examples of the type of disclosures SASB standards are designed to enable in the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section of SEC filings. They demonstrate the use of narrative and analytics to communicate management’s view of known trends and uncertainties, and they’re designed to be consistent with SEC guidance on preparation of MD&A. The Implementation Guide walks readers through a five-stage process that facilitates using SASB standards. Stage three, which discusses performance evaluation and benchmarking practices, is particularly relevant to management accountants. This section of the Guide could also, in conjunction with the research briefs, help management accountants introduce sustainability topics to their organizations.

Additionally, our Fundamentals of Sustainability Accounting (FSA) credential can strengthen the ability of management accountants to advise and influence company leaders regarding some of the most pressing matters that current performance management systems may overlook. The first exam—Level I—focuses on principles and emerging practices of sustainability accounting. The second exam—Level II—focuses on application and analysis.

Finally, in addition to these more pragmatic resources, we offer further detail on SASB and how we work in our “Conceptual Framework” and “Rules of Procedure.” The first describes the objectives, guiding principles, and methodologies that serve as the basis for our work. The second sets forth the process for development, codification, and maintenance of the standards. SASB welcomes feedback on these governing documents through July 6, 2016.

We believe these resources, and of course the standards themselves, support both the evolution of business as it adapts to a changing world and the key role management accountants play in that evolution. We also believe they support one of the most important jobs management accountants do every day: innovating for the future.

June 2016