That brings to mind another cliché: “Our most valuable assets go down the elevator every night.” And while that statement usually applies to employees going home for the night, the case remains the same when employees leave the company: They take with them the knowledge of how they work. Yet most companies don’t see it as valuable enough to retain.

These clichés illustrate the strategic misperceptions surrounding the intangible assets of most businesses today: The work methods of knowledge workers—those once labeled as white-collar employees—represent the majority of business value. There is enormous waste lurking beneath the established norms and approaches in addressing—or more often, not addressing—how knowledge workers get their work done. According to data from The Lab Consulting, where I’m managing director, up to 40% of knowledge work activity can be eliminated. Ignoring this waste reduces earnings in the Fortune 500 by a staggering 14%.

Ironically, the solution lies in what knowledge workers historically delivered to the factory floor—the rational structuring and standardizing of work methods. Put simply: industrialization.

“VIRTUOUS” WASTE

Executives don’t apply industrialization in the office because they consider knowledge work to be fundamentally different from factory work—but that simply isn’t the case. Both types of work have repeatable patterns that can be better organized, documented, and made more efficient.

Consider the example of a global insurer that had more than 40% of its applications for new business arrive with errors and omissions. A manufacturing plant would be incapacitated by inbound error rates this high; the problems would be investigated and reduced. In the virtual “insurance factory,” however, error rates weren’t even recorded. Corrections represented business as usual.

In fact, knowledge workers and their managers often viewed such rework as valuable activity: They felt they were preserving revenue, making the sales force more productive, and serving customers. The waste was seen as virtuous.

After applying the basics of industrialization, however, throughput of the new business group was improved almost threefold. “Assembly lines” were implemented to create a straight, smooth flow of work where previously the company’s existing digital workflow system had simply facilitated inconsistent, zigzag routes for the work. After the assembly lines were sequenced and prioritized, each employee was given detailed instructions. The goal was to standardize best practices and reduce the sevenfold variance in time required to perform identical tasks.

With that in place, a daily dashboard report was developed to track productivity, error rates, and average work time for individual tasks. The result was that interactions among sales staff, customers, and the home office were streamlined, and three-quarters of the inbound errors were eliminated at the source without adding any new technology. Within six months, the new “business factory” was industrialized.

THE ROOT OF DYSFUNCTION

The root causes of waste on the assembly line and in the office are the same: excessive variation, needless customization, ambiguous decision rights, and inadequately documented processes. Both types of work have repeatable patterns, but few knowledge workers acknowledge this.

In the office, valuable knowledge that belongs to the business resides instead with the individual. Whether they want to or not, office workers are forced to carry much of the business’s valuable knowledge in their personal memory. It’s subject to their individual interpretations and personal capabilities. Organizations have vast stores of unwritten tribal knowledge that represent the collective sum of these individual interpretations.

Compared to an industrialized plant, knowledge can’t accrue efficiently or be refined continuously. It can’t be standardized and understood reliably. It can’t easily be transferred to other workers. It can’t be integrated into the design of knowledge work operations and products to improve performance. And it can’t deliver the competitive advantage of the experience curve. This disregard of proven industrialization techniques devalues the basic currency of knowledge work: knowledge.

With industrialization in the plant, on the other hand, decades of accumulated knowledge resides in documents, research findings, and test results. It is built into the workflows, the tools, and the layout of the work area. Work processes and products are jointly designed around the business’s accrued knowledge assets. The workers follow and augment what is already known. Plant employees can change positions from shift to shift, or plant to plant, and consistently deliver output with variance measured in parts per million. The automation that enables such precision requires rigorous standardization of work processes. With industrialization, the whole is enhanced by the sum of its increasingly complementary parts.

INDUSTRIALIZE THE OFFICE

The first obstacle in reclaiming this squandered value is overcoming conventional wisdom, which holds that industrializing the work methods of people in the intangible factories of marketing, finance, or order management is either impossible or radically different from industrializing the work methods of people in a tangible factory.

The delivery trucks in a company’s distribution fleet will be managed more rigorously and efficiently than its sales and marketing campaigns. The difference is that the trucks are long-lived tangible assets with value that is directly obvious and easily understood by anyone. The truck fleet will easily garner investment in detailed, activity-level scrutiny and industrial engineering analysis to ensure optimal fuel mileage, maintenance costs, and liability safeguards.

The same can’t be said about the efforts of sales and marketing teams. The work they do is harder to observe or describe in detail. It comprises competitively valuable intangible assets, but it rarely receives similarly detailed attention. It will more likely draw expense reduction reviews.

One of the world’s oldest, most prestigious global news providers meticulously manages its costs for print and electronic distribution. Industrial engineers monitor the printing presses while data engineers scrutinize online costs and performance. In marketing, the company spends lavishly to survey its customers (in this case, advertisers) about how they define service quality.

Yet these findings are only circulated informally among the senior management team. Individual perceptions of the results aren’t reconciled; each executive is allowed to interpret or rationalize the findings as he or she sees fit. It’s no surprise that the marketing and sales executives maintain dozens of conflicting views about their target customers’ most important purchase-related priorities. Consequently, their campaigns fail to generate increases in new business.

So where to begin? Most definitions of marketing include the terms “customer” and “value.” The first step is to agree on what customers believe is valuable, then connect all business operations to deliver that value effectively. It’s simple but far from easy. Here’s how the news publisher did it:

1. Reconcile Customer Survey Findings: The findings from the survey were reconciled with the disparate, inconsistent perceptions across the leadership teams. Terms such as “quality” were redefined to align with customers’ perceptions of quality.

2. Improve Operations: Procedures were streamlined to reduce pricing errors by sales staff, to standardize procedures for receiving ad materials from customers, and to document more clearly lead time for ad placement.

3. Connect End-to-End Business Processes: The industrial engineers were required to connect their printing plant scheduling with sales and marketing. The engineers had previously sought only to optimize printing plant efficiency, which reduced print costs but also compromised the short-term deadlines customers sought. Within several months, the industrial engineers were able to harmonize printing schedules to meet the lead times delivered by competitors and expected by customers. They were also able to contribute their industrialization thinking to continuous improvement of marketing and sales operations.

THE ASSETS OF KNOWLEDGE WORK

The second obstacle to realizing this value is our understanding of intangible assets. When most business people hear the term “intangible assets,” the first thing to come to mind is likely patents, franchises, copyrights, trademarks, and goodwill. They might even point out that conventional accounting methods currently accommodate these on the balance sheet and that managers have lengthy experience managing such assets. They are correct. But these assets are more appropriately called “intellectual capital,” and they represent a minority of a business’s total intangible assets—generally no more than 25%.

Economists describe the remaining 75% slice of the intangibles pie as “competencies.” These include innumerable line items, such as labor, office expense, and transportation, scattered across the business from sales through Human Resources to research and development (R&D), manufacturing, and customer service. This differs from tangible assets, where the costs of a building or a machine are grouped together logically.

All of the disparate components that constitute competencies are linked in low-visibility business process workflows, customer contact points, and tangible work products, such as orders and correspondence. Most of these can be industrialized just as they are in the factory.

WHERE COMPETITION OCCURS

Digging deeper into the competencies helps uncover the hidden, untapped value. The first segment, general competencies, includes computers, databases, R&D, and general business methods. These aren’t proprietary.

Economists refer to the second segment—the specific, proprietary methods—as “economic competencies.” This segment includes knowledge and practices of both workers and management that are specific to individual firms and even work tasks within those firms. These are a company’s proprietary operational minutiae—tasks, know-how, practices—that provide a competitive advantage.

Most of the day-to-day competitive battles are waged on the fields of general competencies, the easiest segment to industrialize—and the most neglected.

Here’s how that works. Managers will invest to protect the legal instruments that represent the intellectual capital listed as assets on the balance sheet, such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights. And they are always conscious and protective of their proprietary economic competencies.

Yet most businesses face formidable competitors who are equally endowed with similar proprietary competencies—brands, secret formulas, and unique manufacturing methods. Because of this relative parity, the contest occurs in the more tactical general competencies. These are seemingly mundane matters like order processing, promotion management, and plant scheduling flexibility. This is knowledge work.

Think of branded packaged food producers. They all own proprietary, patented product formulas and trademarked brands. Despite the power of a brand, customers face a wide range of options for sodas, soups, and cereals. That means that competitors will gain or lose, not just on brand name alone but also on the effectiveness of their nonproprietary marketing and sales capabilities. They will compete on their ability to win shelf space or secure an end-of-aisle display in a grocery chain.

In practice, this aspect is often one of the least industrialized areas within retailing. Manufacturers have trouble ensuring consistency of pricing and rebates within large accounts, across different customers, and even within similar product categories. Beer deliveries can be synchronized within tight time frames for stores along the same route, but point of sales displays arrive late from marketing.

The failure to industrialize these general competencies is the Achilles’ heel of management. At best, these competencies are managed informally or intuitively. At worst, they are managed by exception—in other words, by firefighting. The fact that the decision rights for these tasks lie within the realm of the historically autonomous knowledge worker makes standardization all the more challenging and threatening.

THE ACCOUNTING BLINDERS

Seeing the potential of industrialization is difficult because it isn’t on the balance sheet. Accounting rules mandate that the firm’s competencies—its people leaving on the elevator every day—appear as expenses on the income statement. This puts valuable intangible assets at a severe perceptual disadvantage. Assets attract attention and investment for industrialization. Even the definition of the term assets includes the words “useful” and “valuable.”

By comparison, expenses are defined with words like “necessary” and “required.” Consequently, “assets” carried on the books as expenses aren’t likely to be viewed as valuable and worth industrialization. Why should anyone invest in an expense? Furthermore, expenses are recurring, creating the perception that reductions deliver annual savings in perpetuity. The irony is that industrialization can reduce expenses further and far more effectively than shortsighted cost cuts.

HIDDEN DRAINS ON VALUE

Managing intangible assets with one-off methods and tribal knowledge drains shareholder value in three ways: overstaffing, no experience curve, and unnecessary capital investment.

Overstaffing. The Lab’s examination of tens of thousands of specific work activities reveals excessive variation in output, needless customization, ambiguous decision rights, and undocumented processes. For the Fortune 500, this translates into $3.6 trillion in lost shareholder value—about an eighth of the total shareholder value of the list.

No Experience Curve. In a factory, knowledge accumulated through costly trial and error is documented, stored, and used continuously to improve assembly lines, products, and routines. Knowledge workers, however, perceive their work as inherently unique. Yet studies such as “Knowledge Workers and Knowledge Work,” by Ian Brinkley, Rebecca Fauth, Michelle Mahdon, and Sotiria Theodoropoulou (The Work Foundation, 2009), show that roughly two-thirds of it is highly repetitive and ideally suited for industrialization. That means approximately 67% of knowledge work could potentially be industrialized!

Unnecessary Capital Investment. The methods of knowledge workers often lead to needless spending. For example, the processes and methods used to design characteristics of operational statistics—or “data elements”—are often poorly documented and loosely enforced. This means that the operating data captured, stored, and reported isn’t helpful for management. It’s easy to blame these deficiencies on existing IT system capabilities—which spurs spending on system upgrades. Afterward, these unhelpful data elements are imported into the new system. The one-off knowledge work methods that originally designed the unhelpful data elements remain in place, perpetuating the cycle.

WE ALREADY KNOW WHAT TO DO

Discovering what your knowledge workers are actually doing every day has become more important than ever as intangible assets have risen to dominance.

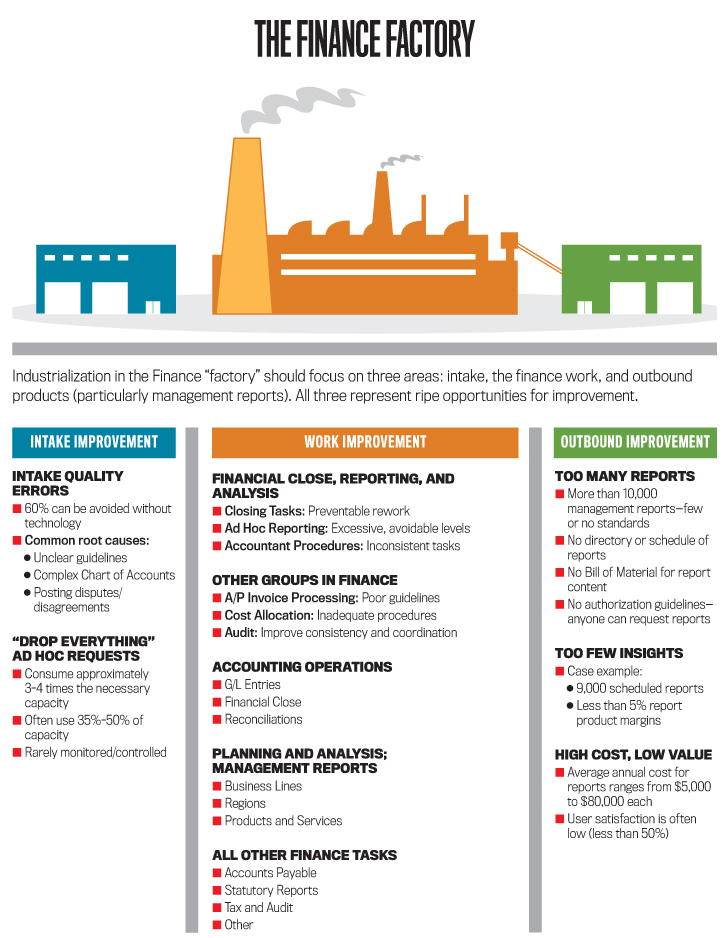

In 1975, only 17% of S&P firms’ assets were intangible. In 2015, those intangible assets had grown to a staggering 84%. Our ability to account for and manage this sea change lags far behind. This may well explain the productivity paradox that was noted decades ago: Investment in computers didn’t increase office worker productivity. Computers automate but do not industrialize work. That can only be achieved through conscious, engineering-style effort. So today, knowledge workers still work the same way, just a bit faster.

Most businesses already possess the sophisticated capabilities to standardize and specialize—to industrialize—the work methods of their people assets. Now all that remains is to adapt those capabilities to knowledge workers.

Peter Drucker, the management guru who coined the term “knowledge worker,” said in the late 1990s: “The most important contribution of management in the 20th Century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st Century is similarly to increase the productivity of the knowledge worker.” Perhaps we need another Industrial Revolution, but this time with the focus on the largest, least studied segment of employees in today’s advanced economies—knowledge workers.

January 2016