Two of a manager’s most important responsibilities are to motivate and to provide direction for his or her team. Without these two qualities, the manager or the team won’t be very successful.

The concept of providing direction is easy to grasp. A manager’s responsibility is to ensure that his or her team works toward achieving the company’s objectives, goals, mission statement, and so on. Motivating a team is more difficult. While on a fundamental level individuals can motivate themselves from within, management is responsible for building a work environment that keeps employees motivated and pushes them to excel. This can happen through incentives, formal or informal recognition, and management style.

One of the best expositions of motivation at work that I’ve seen recently comes from Daniel Pink’s Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Pink posits that once people have a sufficient income to live comfortably, they need three things to keep them motivated at work: autonomy, purpose, and the ability to gain mastery. Pink’s theory is a modern exposition of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—people want to develop, to be creative, to solve problems, and to grow (or in Maslow’s terminology, to “self-actualize”).

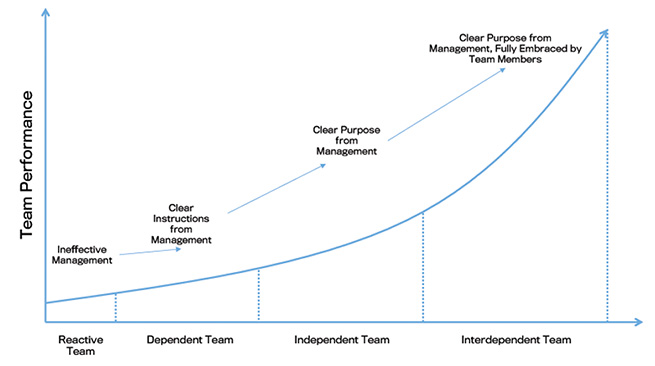

We can apply this thinking to understand how a manager can develop a high-performing team (i.e., a team that’s motivated and achieves exceptional results). There are four stages (levels) that a team can go through, moving from a low-performing, reactive team and advancing toward a high-performing, interdependent team. Some teams could be formed at, say, level 3 and move upward or downward from there, while others may need to go step by step. (See Figure 1 for a graphic representation of each stage of a team.)

REACTIVE TEAM

This is the lowest-performing team level. The team has ineffective management, lacks organization and/or coordination, and doesn’t work toward common goals (either of the team or of the overall organization). It’s likely transactional in its interactions with the organization (i.e., the team is asked directly to do something and executes the request). Additionally, since the team has no common goals and little autonomy, team members aren’t motivated to do anything more than simply complete the task at hand. In this case, the team manager exists in name only. He or she does little to formally or informally influence the team, and, as a result, the team’s performance is poor.

DEPENDENT TEAM

This is a step in the right direction. In this case, the manager provides clear and prescriptive instructions to the team, and the team members carry them out. In specifying both the “what” and the “how,” the manager ensures that there’s no misunderstanding and that the tasks are carried out exactly as he or she wants. While this ensures the task is completed, this stage of “teamwork” misses opportunities for understanding and effectiveness because it doesn’t leverage the knowledge and expertise of the individual team members. Instead, it assumes that the manager is the expert, and the team members play a purely executional role. On the other hand, the manager finally takes on a directive role, closing the gap from a reactive team. Yet there’s still very little autonomy or purpose given to the team—they’re simply told what to do and how to do it. This ultimately results in a poorly motivated team.

INDEPENDENT TEAM

In an independent team, the manager provides purpose, and the team members develop what to do on their own in order to achieve the objectives. Said another way, management specifies the “what,” and the team members independently develop the “how.” This acknowledges the team members’ important role to not only execute but also to improve processes and solve problems, better leveraging the expertise and experience of the full team rather than just the manager. In this team setting, functions are balanced, and the team trusts each individual’s area of expertise and responsibility. This has been developed extensively in the Kaizen concept in Lean production but can equally be applied to services and support functions. Additionally, an independent team operates with higher levels of autonomy and purpose, which leads to a motivated team and creates a virtuous circle of performance and motivation.

Despite the strengths of an independent team, there are still challenges, namely that it’s independent by nature. While the team members work toward a common purpose, they also work in silos and compete with each other for recognition and advancement. There’s limited cross-fertilization of ideas, approaches, and methods, which holds back performance from its optimal level.

INTERDEPENDENT TEAM

In this most successful stage, management sets a clear purpose, and it’s fully embraced by the team members, who work toward it together. Said differently, management specifies the “what,” and the team members take the initiative to interdependently develop the “how.” Most important, the team recognizes that working together creates more value for the organization than working in silos, and collaborating with each other is better than challenging each other. The team has bonded, and individuals trust each other to deliver a high-quality product. They exhibit a positive attitude toward each other and approach challenges as opportunities. The feedback loop provided by team members who challenge one another can also be applied to the interaction between team members and management. In truly high-performing teams, team members can openly challenge management about the team’s purpose and anything else. A healthy dissatisfaction with the status quo ensures that the team constantly works to bring the most value to the organization.

By ensuring that your team has embraced a clear purpose and by encouraging team members to work together and to challenge each other (and management), you and your team can deliver organizational value more effectively.

September 2015