At the same time, estimates of fraud generally range from 3% to 5% of total healthcare costs, with estimates of billing errors as high as 21%. Despite using electronic data interchange (EDI) and advanced controls, the healthcare industry spends approximately 12% of revenue on billing and collection costs. Since reimbursement is often paid directly to the service providers—hospitals and physicians—errors and fraudulent billings are rarely visible to patients or the general public.

The costs of fraud and errors are borne by everyone through higher insurance rates. If the United States could reduce the costs of errors, fraud, and billing and payment administration by only 10%, a significant reduction in healthcare costs would be realized.

In terms of traditional procurement processes, the patient is the purchaser, and the hospital or physician is the vendor that provides services and submits invoices to the insurance company for payment.

Invoices go directly from provider to insurer, and, in some cases, the invoice also goes to the patient at the same time. But the insurer/payer doesn’t wait for confirmation from the patient that the services were, in fact, performed before remitting payment to the provider. In general, the insurer accepts the patient’s registration with the provider as proof of services and doesn’t require further confirmation after services are received and before remitting payment.

Yes, healthcare consumers pay copays, percentages, premiums, and deductibles, yet patients are essentially excluded from an important segment of the payment process. By not communicating with the patient after services are rendered, a number of provider frauds can be perpetrated. In fact, the U.S. Attorney General and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reported in June 2015 that they had charged 243 providers across the country with Medicare fraud totaling $712 million.

These fraudulent billings were enabled by circumventing a basic payment control—that is, acknowledgement of receipt of services before the insurer makes the payment. Perhaps third-party payers could reduce the risk of making erroneous payments by allowing patients to confirm they received the services the provider is billing. This is similar to the acknowledgement of receipt in traditional procurement processes used by many Accounts Payable departments of business entities.

THE COST OF BILLING ERRORS AND FRAUD

A recent review of certain Medicare and Medicaid services by the Office of the Inspector General noted billing errors in more than 20% of physician charges for evaluation and management services. If this same error rate were present in all billings to Medicare and Medicaid ($1.04 trillion in 2013, according to the CMS National Health Expenditures Fact Sheet), billings of more than $200 billion would contain errors. Applying the same error rate to the entire $2.9 trillion in U.S. healthcare spending results in more than $400 billion in erroneous medical charges.

In its “2014 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse,” the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) identified healthcare as one of the top four industries impacted by fraud. Billing, corruption, and expense reimbursements represented the top three vulnerabilities. The departments at fault for most of the reported cases were accounting, operations, and sales. The major weaknesses included (1) lack of internal controls, (2) override of existing internal controls, and (3) lack of management review.

We may never know the full financial impact of healthcare fraud. Most federal control efforts are directed at fraud perpetrated against insurers rather than at patients/consumers or providers. Since some fraud is never reported—either because it goes undetected or perhaps an organization fears bad publicity—the actual amount is unknown.

Although many factors contribute to healthcare fraud, we suggest that eliminating the patient from the payment process until after payment is made facilitates erroneous/fraudulent billing from the provider to the insurer. The National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association’s Anti-Fraud Resource Center says the basic fraud or error is simply that providers overbill for services that weren’t performed—in other words, a false claim scheme. Other false claims and provider billing errors include unbundling, double billing, and upcoding. Requiring patient approval before payment could help reduce several provider frauds.

THEN AND NOW

The creation of insurance in the early part of the 20th Century addressed a specific need that arose with the increasing cost of healthcare. Insurance companies spread the risk and cost of extended or debilitating illnesses for an individual over a large number of people. This risk spreading helped alleviate the financial burden of an injury or extended illness that would cause a person to be unable to work. Insurance could cover large, major medical bills but initially didn’t cover preventative services. Patients would pay their bills, which were much lower than today, and then seek reimbursement from their insurers.

As employer-provided insurance became more commonplace, a majority of the U.S. population had medical coverage by 1950. During the 1950s and early 1960s, healthcare costs were somewhat stable, and benefits for employees and retirees weren’t significant. The total cost of healthcare as an employee benefit was manageable and received little attention.

But as costs increased, patients could no longer afford to pay the doctors or hospitals until they received reimbursement from their insurance. Providers would experience a significant delay between the time of service and ultimate receipt of the payment. In the late 20th Century, health insurance companies agreed to speed things up by paying providers directly. This was the first step in removing the patient from the payment process. As insurance products continued to evolve, and as Medicare and Medicaid costs strained government budgets, the consumer became further disconnected.

Today, insurers pay providers directly. The price between the insurer and the provider is determined without patient involvement. While some consumers see copies of the bills submitted to insurers, they aren’t expected to confirm that all the itemized services were received before payment is made. Patients are often only aware of their copays and deductibles.

In a modern billing process, billing and verification may be conducted using EDI. The provider bills the insurance company, and the insurer processes the bill using sophisticated analytical tools and either remits or denies payment. After payments are made, the insurer sends the patient a statement and explanation of benefits (EOB) showing the amount paid and the allowable amounts under his or her coverage.

Finally, the provider sends the patient a bill that reflects the charges, the amounts paid by insurance, and the remaining amount due, if any. The EOBs note the amounts allowable toward a patient’s or family’s deductible and any copays required, in-network and out-of-network charges, and the final amounts the patient is ultimately responsible to pay. Patients typically pay their copays and often their portion of the charges at the time of service at the provider’s office, but the reconciliation statement or EOB arrives weeks or sometimes months later. Some patients scrutinize these notifications closely, but others don’t, which provides an opportunity for an inappropriate or inaccurate bill to be paid by the insurer. A possible alternative would be to have the patient confirm receipt of the service and confirm to the insurer that the billing appears appropriate.

Federal rules require at least 80% of all claims from physicians to be submitted electronically. Medicare and Medicaid will generally accept only electronic claims. Providers submit claims through a clearinghouse that audits the data and corrects errors before submitting claims to insurers.

The system does not confirm the details of claims with patients; it only confirms that amounts are correct based on the list of services the provider submitted. Sending a notice to patients to confirm services could easily become part of the review/scrubbing process. Most patients won’t know the amount to which the provider and the insurer agreed, but they should understand what services they received.

Having the patient confirm receipt of service as the claim is processed through the clearinghouse will reduce the chance that an improper bill is paid. This would increase the insurer’s confidence that the service was legitimately performed and coded correctly before it makes the payment. We believe that the simple control of increasing patient involvement in the billing process can reduce errors and frauds at very little incremental cost.

LESSONS FROM BUSINESS

In traditional procurement operations, the process begins with someone preparing and approving a requisition for a product or service. The approved requisition is sent—often electronically—to the Purchasing department, which submits a purchase order to an approved vendor. A copy of the purchase order is forwarded to the Accounts Payable group in the Accounting department. When the item or service is delivered, an employee (other than the requestor) verifies and acknowledges receipt and forwards a copy of the receiving report to Accounts Payable.

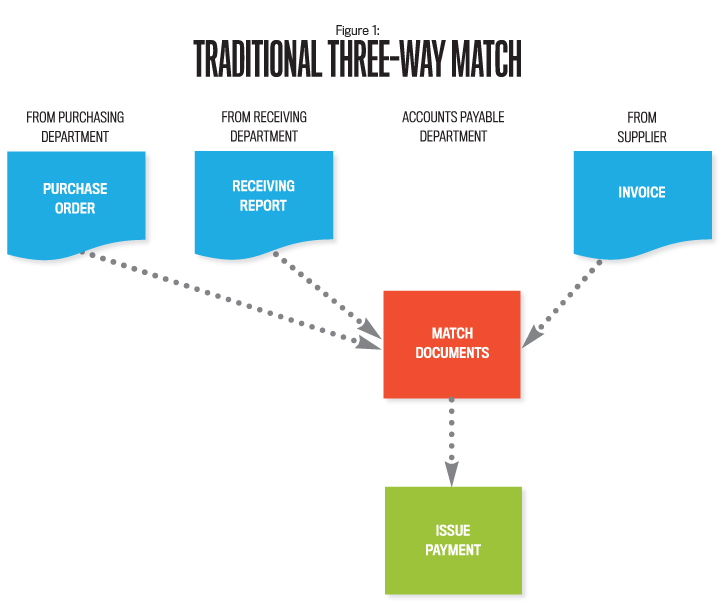

To request payment, the vendor submits an invoice to Accounts Payable, which compares the invoice to the purchase order and receiving report for accuracy and agreement. Discrepancies such as amounts, quantities, or approvals are investigated prior to remitting payment. Reviewing these documents—traditionally called the “three-way match”—is a component of the organization’s internal control system to detect errors and fraud (see Figure 1). This verification process guards against ordering or receiving goods without a properly approved requisition or purchase order.

Verification is equally important for purchases by individual consumers. For example, prior to making a payment, individuals who order products online should verify that the items ordered and received agree with the amount the retailer billed. This is also appropriate for services such as home renovations, automobile repairs, or utilities.

We suggest that patients receiving healthcare services could similarly review and concur with billed hospital and physician charges before third-party payers issue payments.

PROPOSED IMPROVEMENTS

To improve the payment process and reduce overpayments from either unintentional errors or intentional fraud, an opportunity exists to involve the patient in the receipt acknowledgment step before the insurer remits payment. Again, it should be relatively easy since most, if not all, reimbursements are processed electronically.

When the medical provider submits the bill to the insurer, the patient could also receive an electronic copy (see Figure 2). The insurer wouldn’t pay until the patient indicates that he or she did indeed receive the itemized services.

Providers might object to this additional review because it could potentially slow reimbursements, but electronic communication could be used to secure a patient’s payment approval without a significant slowdown. With health insurance now required by law in the U.S., most people will be covered by some form of insurance. Providing an incentive, such as reduced deductibles on that element of service or reduced premium payments for catching errors, could encourage patient response.

The healthcare industry is already aware of the three-way match. Finance departments in hospitals implement the process for Accounts Payable. Many providers use it to reduce medication errors. Advances in technology, including RFID (radio frequency identification) tags, barcoding, and scanning devices—as well as smartphone apps—make the match easier and faster to implement.

With current IT advances, particularly in wireless technology, involving the patient in the payment-for-services process need not significantly delay payment to providers.

IMPROVING PATIENT UNDERSTANDING

Lack of consumer knowledge and understanding of healthcare services and costs is a major issue. Byron Hollis, director of Blue Cross Blue Shield’s National Anti-Fraud department, emphasized that increased consumer knowledge was key to mitigating healthcare fraud.

The three-way match process in a typical business is applied by employees who understand the quantity, quality, and prices of products received, but the effectiveness of applying it to healthcare patient billing is reduced by the lack of involvement and sophistication of the healthcare consumer. Two emerging trends are expected to help educate healthcare consumers: high-deductible plans and bundling charges.

High-Deductible Health Insurance Plans: One opportunity for businesses to raise awareness and understanding of healthcare costs is for employers to use high-deductible insurance plans. Consumers pay attention to purchases that cost them the most money, and high-deductible plans pass more of the initial healthcare costs on to consumers. High-deductible plans may offer a solution and encourage more customer involvement and understanding.

High deductibles are often combined with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), and a growing number of healthcare plans are consumer-directed. A May 2012 study by research organization RAND noted that these plans “could reduce annual health care spending by about $57 billion” as a result of greater customer involvement. Since consumers are paying for more services out of their own pocket before insurance pays, demand for certain services has decreased. Related benefits of the increased consumer involvement in the payment process could include more-sophisticated healthcare consumers. Greater involvement in the payment process may begin to reverse consumers’ disconnect from the process, which will increase oversight and control.

Bundling Provider Charges: “Bundling” is a significant modification to the current billing process that would streamline information to the consumer and make billing much more transparent and understandable. Being encouraged by Medicare, bundling results in a single simplified patient bill that covers all services and supplies from every provider involved in a particular service event.

Using surgery as an example of a service event (i.e., the hospital stay), the services of all the physicians involved, supplies, and medications would be covered by a single charge to the patient. Once bundling becomes standard practice, patients will be able to understand the services for which they’re billed and can approve payments more readily.

THE ROLE OF MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANTS

Management accountants are in a position to be major players in dealing with issues related to healthcare costs. We should examine these issues in light of the impact on our duties and responsibilities. Here are some key assumptions, if not certainties, to keep in mind:

- Healthcare costs presently are significant and will continue to increase.

- Errors and fraud related to healthcare costs are significant components of total healthcare costs.

- Good internal controls help reduce errors, fraud, and excessive charges.

- Users of healthcare delivery systems need to be better educated about the true cost of healthcare and to help reduce moral hazard (increased consumption that results when insurance is involved).

- The recent Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and future legislation will continue to add new complexity to healthcare processes.

Specifically, management accountants have the skills to identify the cost levels and trends to be utilized by decision makers. They also are well-qualified to bring unique views to the design of control systems. Further, they can play a major role in educating employees and their dependents who use healthcare provided and paid for by employers.

In summary, internal controls play an important role in minimizing erroneous or fraudulent healthcare billing. Enhancements to payment processes, which could play a role in controlling healthcare costs, should interest all employers, providers, patients, and third-party payers. As the landscape continues to change, revisions to internal control processes will be required.

Perhaps insurers went too far in removing patients from the payment process to speed up reimbursement to providers. For now, increasing patient participation in the payment process appears to be a step in the right direction. Insurers and billing organizations may be well-served by revisiting the traditional accounting three-way match process, once again requiring patients to verify that billed products and services were received.

Operationally, a match process could be utilized selectively for prescribed dollar amounts in excess of a given level (for example, charges more than $1,000). With current technology, involving patients in the payment process could result in little, or no, disruption in the process.

September 2015