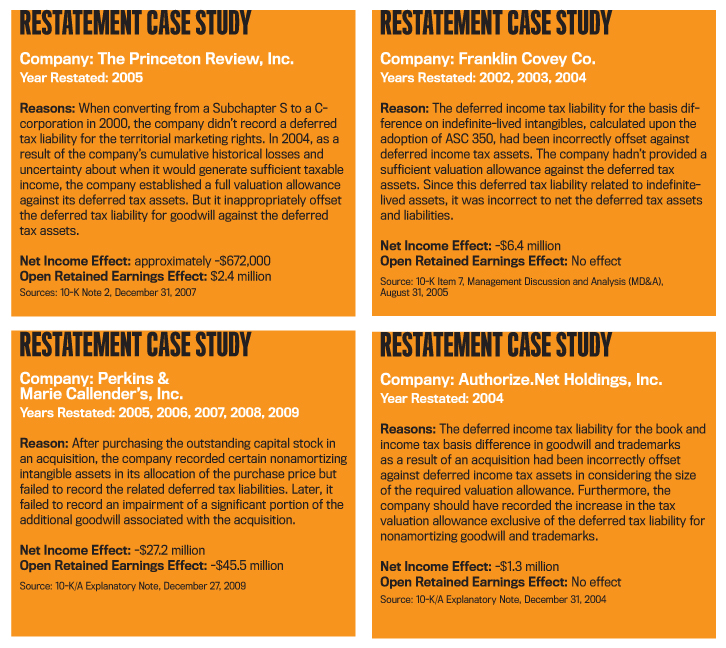

Accounting for income taxes is one area that leads to a high percentage of total restatements. According to the Ernst & Young Technical Line paper, “Lessons Learned from Our Review of Restatements,” accounting for income taxes was the largest cause for restating in a sample of 2011 restatements and was the second-largest cause in a sample of 2010 restatements. We examined restatements occurring between 2005 and 2010 related to accounting for income taxes and identified by Audit Analytics, a Sutton, Mass.-based independent research firm. Seventeen of the identified firms restated their financial statements due to two problems: (1) improper recording of deferred taxes related to indefinite-lived intangibles acquired in mergers and acquisitions and (2) mishandling of deferred tax assets and liabilities on indefinite-lived intangibles in determining the valuation allowance.

Companies—and their CFOs—engaging in mergers and acquisitions need to be familiar with the associated tax accounting implications if they want to avoid similar restatements. To help navigate these issues, we’ll take a close look at accounting for income taxes related to indefinite-lived intangible assets in the context of business combinations, as well as the determination of the valuation allowance.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM

Because the restatements occur as a result of mergers and acquisitions, let’s briefly review the area of business combinations and its consequences in accounting for income taxes. Remember that the federal tax law rules for business combinations are complex, and this overview isn’t meant to be a comprehensive discussion of those rules.

Mergers and acquisitions take one of two general forms: a stock acquisition or an asset acquisition. Depending on the structure of the merger and the consideration paid to the target’s shareholders, the business combination is either a tax-free reorganization or a taxable transaction.

Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §368, “Definitions Relating to Corporate Reorganizations,” and Treasury Regulation 1.368 contain the tax-free reorganization rules that exempt six specific corporate combinations from taxable gain recognition at the time of the reorganization. Four of them (Types A, B, C, and E) affect the accounting for income taxes with indefinite-lived intangibles.

In Type A or B reorganizations—which are nontaxable business combinations under IRC §368(a)(1)(A) and IRC §368(a)(1)(B), respectively—the acquiring company assumes the carryover (historical) basis of the acquired company’s assets and liabilities. When a taxable stock acquisition occurs without election of IRC §338, “Certain stock purchases treated as asset acquisitions,” the purchaser receives the target’s stock with a tax basis “stepped up” to fair market value, but the assets retain their carryover basis. In taxable asset acquisitions and taxable stock acquisitions with a §338 election, the acquiring company is allowed a “stepped up” basis of all assets and liabilities to fair market value.

IRC §1060, “Special allocation rules for certain asset acquisitions,” orders the allocation of purchase price based on seven asset classes. This allocation requires distributing the purchase price to the five classes of tangible assets, with the remainder distributed to intangibles. Intangible assets acquired in taxable asset acquisitions and taxable stock acquisitions with a §338 election would be considered intangible assets under IRC §197, “Amortization of goodwill and certain other intangibles.” These assets include many of those considered to be indefinite-lived intangible assets for financial accounting purposes, including goodwill, trademarks, and franchises.

For taxable asset acquisitions and taxable stock acquisitions with a §338 election, §197 intangibles are amortized over a 15-year period regardless of their useful life, including goodwill. But when a company acquires these same intangibles in a nontaxable transaction or a taxable stock acquisition without a §338 election, they aren’t amortizable under IRC §197.

VALUING INDEFINITE-LIVED INTANGIBLES

All business combinations under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are required to use acquisition accounting whether they involve a stock acquisition or an asset acquisition. Under acquisition accounting, all identifiable assets acquired in a business combination (including intangibles other than goodwill) would be recorded at their fair values on the date of acquisition under FASB Accounting Standards Codification® (ASC) paragraph 805-20-30-1.

When a company acquires goodwill in a business acquisition, the company initially measures it as the excess of the consideration paid over the fair value of the net identifiable assets on the date of acquisition. A publicly traded company holding goodwill doesn’t amortize it (see ASC paragraph 350-20-25-1) but instead periodically impairment tests it (see ASC paragraph 350-20-35-1). Privately held companies holding goodwill can elect to amortize it over a period not to exceed 10 years (under ASC paragraph 350-20-35-63). Other indefinite-lived intangible assets aren’t amortized for financial statement purposes (see ASC paragraph 350-30-35-1) but rather are periodically impairment tested (see ASC paragraphs 350-30-35-15 through 350-30-35-17), regardless of the type of entity that’s holding the asset.

At the time of the acquisition, a company must recognize deferred tax assets and liabilities related to the acquired assets and liabilities and also recognize any related valuation allowance (see ASC paragraph 805-740-25-2). In addition, a deferred tax asset or liability related to any difference between the book and tax basis of indefinite-lived intangibles, other than goodwill, must be recorded at the time of acquisition—regardless of whether the assets are tax deductible or not (see ASC paragraph 805-740-25-3).

In general, book and tax basis shouldn’t differ in transactions in which a “step-up” basis is taken for tax purposes (taxable asset acquisitions and taxable stock acquisitions with a §338 election), because the assets would be recorded at fair value for both book and tax purposes and wouldn’t initially generate deferred tax assets or liabilities. For transactions in which the assets have carryover basis for tax purposes (nontaxable transactions and taxable stock acquisitions without a §338 election), a deferred tax liability related to any excess book over tax basis—or a deferred tax asset related to any tax over book basis—would be recorded at the time of acquisition. A company must include these deferred tax assets and liabilities in the calculation of goodwill for financial statement purposes.

A deferred tax liability would also be recorded for subsequent amortization deducted on acquired indefinite-lived intangible assets that fall under IRC §197 (that is, assets acquired in a taxable asset acquisition or a taxable stock acquisition with a §338 election). The deferred tax liability would remain on the books until the asset becomes impaired and is written down. At that time, the deferred tax liability would be decreased or removed from the books, depending on the amount of the impairment.

The subsequent accounting is more complicated for indefinite-lived intangible assets that aren’t tax deductible—that is, assets acquired in a nontaxable transaction or a taxable stock acquisition without a §338 election.

For nondeductible indefinite-lived intangible assets, a deferred tax asset or liability will be recorded for the difference between the book basis and the tax basis of the asset. If impairment occurs for financial accounting purposes, the deferred tax asset or liability will be adjusted to reflect the updated difference between book basis and tax basis.

HOW TO HANDLE GOODWILL

The initial accounting for income taxes related to goodwill differs on whether the goodwill is tax deductible or not and whether the tax basis exceeds the book basis or vice versa.

No deferred taxes are recorded when nondeductible goodwill is acquired. A permanent difference results when the goodwill is impaired (if held by a publicly traded company) or amortized (if held by a privately held company) for book purposes. The company must split tax-deductible goodwill into two components (see ASC paragraphs 805-740-25-8 and 805-740-25-9). Component 1 goodwill is the amount of goodwill that has the same book basis and tax basis. For Component 1 goodwill, publicly traded companies would record a deferred tax liability when the tax deduction is taken and then reverse it when the goodwill is impaired for book purposes. Private companies would record a deferred tax asset for the excess of book amortization over tax amortization for the first 10 years and then reverse it over the next five years.

Component 2 goodwill relates to the difference between book and tax basis. If the Component 2 goodwill is an excess of book goodwill over tax goodwill, the company doesn’t record any deferred taxes, and the subsequent impairment or amortization for book purposes will result in a permanent difference. If the Component 2 goodwill is an excess of tax over book goodwill, the company must record a deferred tax asset at the time of acquisition, which is then reversed as the company takes tax deductions. Recording the deferred tax asset at the time of acquisition will create an iterative (circular) calculation of book goodwill because the creation of the deferred tax asset will reduce the amount of goodwill recorded for book purposes.

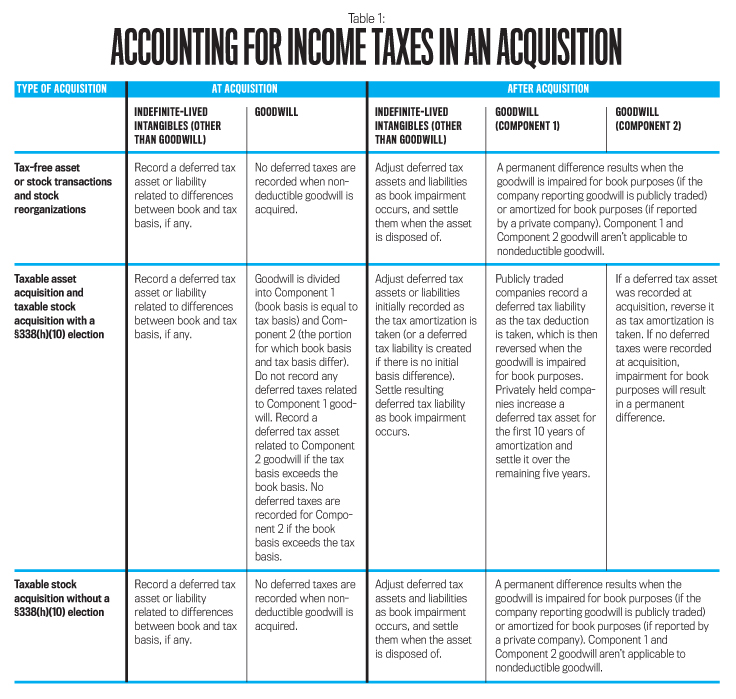

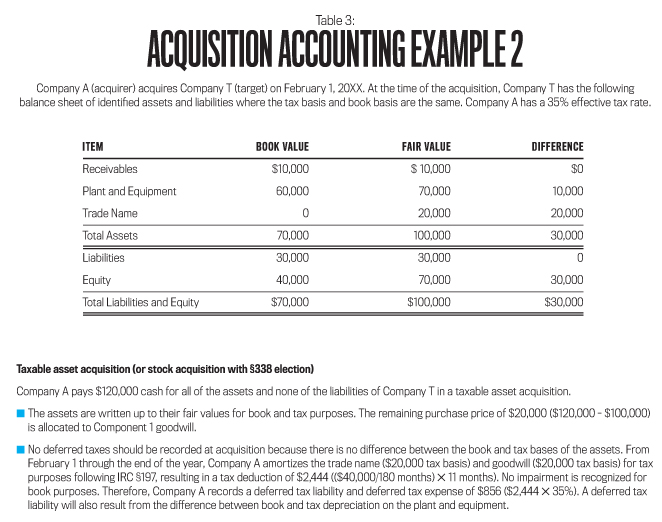

Table 1 summarizes the implications of accounting for taxes, and Tables 2 and 3 show examples of proper acquisition accounting.

VALUATION ALLOWANCE ISSUES

If it’s more likely than not that the tax benefit won’t be fully recognized, then deferred tax assets should be reduced to net realizable value by a valuation allowance (see ASC subparagraph 740-10-30-5(e)). Future realization of a tax benefit from a deferred tax asset depends on sufficient future taxable income of the appropriate character. Future realization of a tax benefit from a deferred tax asset requires sufficient future taxable income to be offset by the future deduction. Additionally, the future taxable income must be of the appropriate type (i.e., character) to be able to utilize the deduction.

It’s important that companies consider the reversal patterns of temporary differences in assessing the need for a valuation allowance, including the particular year in which the temporary differences result in taxable or deductible amounts. The reversal pattern shows the year in which the temporary differences will reverse when assessing the need for a valuation allowance (see ASC paragraphs 740-10-55-18 and 740-10-55-19). The reversal pattern associated with an indefinite-lived intangible asset is unknown because reversal is contingent upon a future event. For example, a deferred tax liability associated with goodwill won’t reverse unless the goodwill is impaired. Existing deferred tax liabilities associated with indefinite-lived intangibles shouldn’t be considered a source of future taxable income in determining the necessary valuation allowance because the timing of the reversal is uncertain. If a company uses deferred tax liabilities associated with indefinite-lived intangibles as a source of future taxable income, it results in an understatement of the valuation allowance and an overstatement of net income.

AVOIDING RESTATEMENTS

When engaging in mergers and acquisitions, the CFO must consider the tax accounting implications associated with indefinite-lived intangibles to avoid having to restate financial statements. The classification as a stock or asset transaction and whether the transaction is tax-free or taxable determines the tax accounting implications. In general, taxable asset acquisitions and stock acquisitions with a §338 election don’t initially result in recording deferred taxes on indefinite-lived intangibles because the basis is “stepped up” to fair value for book and tax purposes. A deferred tax liability is recorded as amortization, deducted under IRC §197, and will be reversed upon impairment of the indefinite-lived intangible assets for book purposes. In contrast, tax-free transactions and taxable stock acquisitions without a §338 election require recording the deferred taxes on indefinite-lived intangibles at the time of the transaction because the basis is “stepped up” to fair value only for book purposes.

If indefinite-lived intangibles are present, the CFO must carefully consider the determination of the valuation allowance. Specifically, the deferred tax liability associated with indefinite-lived intangibles should not be considered as a source of future taxable income when determining the appropriate valuation allowance since the timing of the reversal is unknown because it’s dependent upon the impairment of indefinite-lived intangible assets for book purposes.

November 2015