Considering that the FASB doesn’t impose an Asset Capitalization Threshold (ACT) on companies, we set out to discover whether there was any sort of consistency in ACT choice. To that end, we distributed a multiquestion survey to financial leaders across a broad range of large, mostly public, companies. What we discovered surprised even us, and it wasn’t what we had expected.

ENTERING UNCHARTED TERRITORY

As the old saying goes, sometimes something very valuable can be found “right under our noses.” In this article, we’ll share our latest research into a fundamental accounting practice that has significant bearing on reported periodic net income but hasn’t been discussed widely. Every company, private and public, has an Asset Capitalization Threshold. As such, contemporary ACT practices should be of serious interest to several important stakeholders, including but not limited to, internal and external financial analysts, controllers, and regulators.

Management accountants and those involved in financial planning and analysis regularly use reported net income to make a variety of decisions, including which business units or segments are more profitable than others, and to assess the financial health of customers or suppliers. Therefore, consistency of ACT within a company is critical. Controllers should be very interested in how their company’s ACT compares with that of their peers, with a view toward coherent benchmarking. Regulators, too, should be interested in supporting disclosures that actually improve transparency and clarity regarding reported periodic earnings without increasing the cost and complexity of compliance. The disclosure of ACT in the notes to financial statements would satisfy these criteria and could even improve the public image of the accounting profession.

SHEDDING MORE LIGHT ON ACT

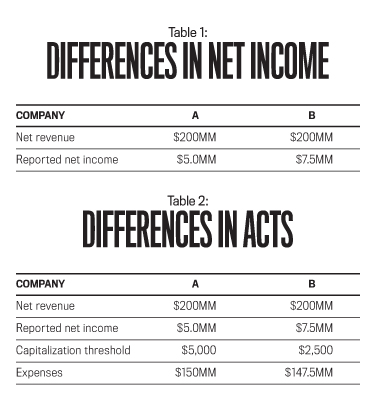

Why is understanding ACT practices important today? To help answer this question, we’ll present a simple illustration of ACT in two companies.

For this example, assume that the two companies shown in Table 1 are identical in every way, yet Company B reports net income 50% greater than that of Company A. How can this be possible, assuming that this difference isn’t a function of inventory cost flow assumption options, choice of depreciation/amortization practices, or any of the “usual suspects”?

Some perspective will prove valuable before we address the question. FASB Concepts Statement No. 8 includes authoritative guidance on “Enhancing Qualitative Characteristics.” The Statement indicates that comparability, verifiability, timeliness, and understandability are qualitative characteristics that enhance the usefulness of information that’s relevant and faithfully represented. These characteristics also may help determine which of two ways should be used to depict an economic phenomenon if both are considered equally relevant and faithfully represented.

The FASB states that “Comparability is the qualitative characteristic that enables users to identify and understand similarities in, and differences among, items. Unlike the other qualitative characteristics, comparability does not relate to a single item. A comparison requires at least two items…Consistency, although related to comparability, is not the same. Consistency refers to the use of the same methods for the same items, either from period to period within a reporting entity or in a single period across entities. Comparability is the goal; consistency helps to achieve that goal.”

In our view, ACT practices are impacted by both consistency and comparability considerations, which give rise to several concerns that will surface in detail later. Here’s just one to whet your intellectual appetite: How can financial analysts rely on reported net income, earnings per share, and other net-income-based performance measures if individual companies in the same industry have different ACTs? Additionally, how can we not avoid distortions in reported business valuations if there’s a lack of transparency with respect to ACTs?

Now back to our sample companies, A and B. As shown in Table 2, they have different ACT conventions, which means, everything else being equal, their results of operations will also be different—even though both companies are the same in every other way.

Now let’s drill down a bit. Based on each company’s ACT selection, if Company A and Company B each purchase $3,000 in equipment, Company A would expense it and Company B would capitalize it. Company A’s net income would be lower than Company B’s by $2,700 after considering depreciation for year one and assuming an equipment life of 10 years with no salvage value. The $2,700 would contribute to the difference in net income between Companies A and B.

At this point, we should note that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and government accounting regulators have set guidelines for asset capitalization. But these have no bearing on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP), International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and the related general purpose financial statement preparation that’s the focus of our study.

WHAT OUR SURVEY REVEALED

We surveyed participants at a CFO Rising conference workshop that one of us conducted recently. The respondents represented 39 different companies:

Industries. The respondent companies belong to a broad range of industries, which we grouped into four categories: Financial Services (five companies), Manufacturing (five companies), Nonfinancial Services (15 companies), and Other (14 companies).

Revenue Levels. Two-thirds of the sample (26 companies) earn revenues greater than $1 billion annually, and 13 companies earn less than $1 billion.

Ownership Categories. While our sample included both publicly traded and privately held corporations, public companies made up almost two-thirds of the entire sample (25 companies).

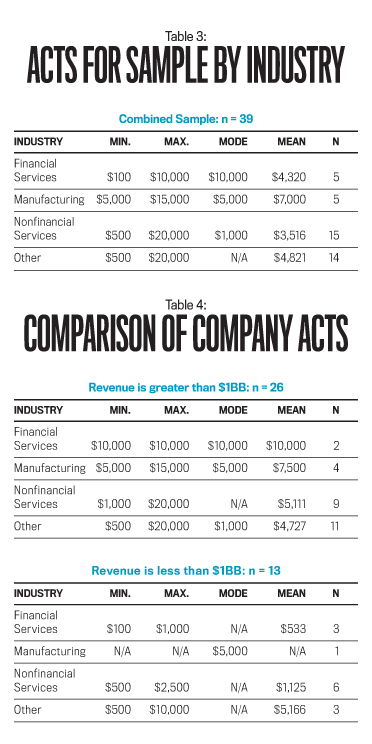

Table 3 displays ACTs for the combined sample divided by industry. Included are the minimum reported ACT, the maximum reported ACT, the most commonly reported ACT (the mode), and the mean. The number of companies in each industry is listed in the far right-hand column.

As you can see, there’s great diversity in ACT choice, with some thresholds exceeding others by as much as 4,000%! Even in Manufacturing, where the least diversity exists, maximums are triple the minimums reported.

To better understand why ACTs are so divergent, we divided the sample by revenue level to see whether ACTs are more consistent between companies of similar sizes. For the most part, we found that they aren’t. Great disparity exists, too, between companies earning more than and less than $1 billion in annual revenues. The differences appeared slighter, however, in our sample of smaller companies. See Table 4.

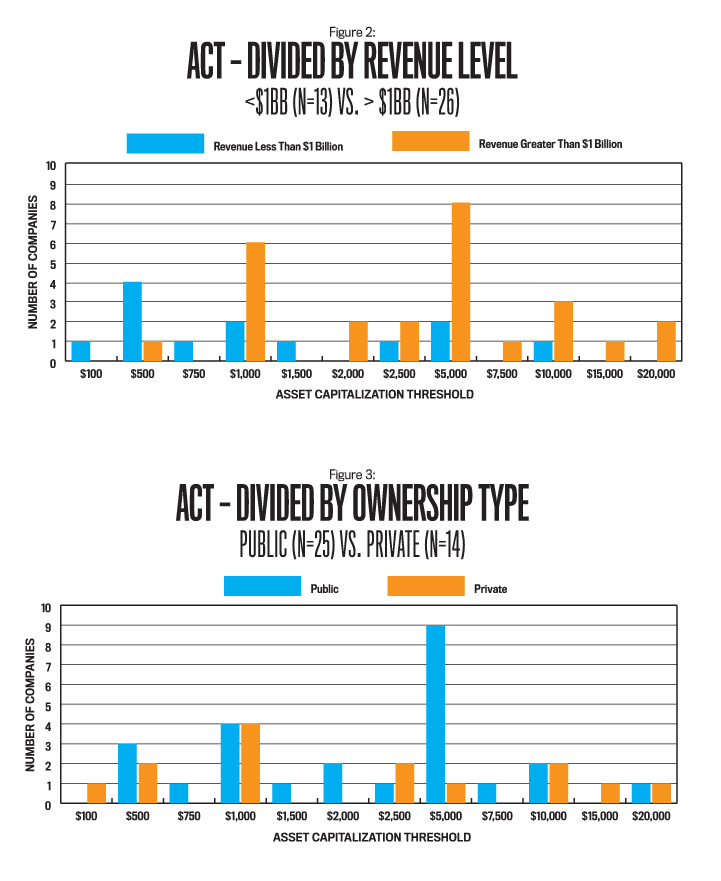

Figure 1 is a breakdown of Asset Capitalization Thresholds by company. It shows that roughly half settled on an ACT of $1,000 or $5,000, with just a few outliers choosing $10,000 or more.

SOME PREDICTABLE PATTERNS

As you would expect, the smaller companies reported the smallest thresholds, whereas the largest ACTs belong to the larger companies. But as Figure 2 illustrates, there’s still an extremely wide range of ACTs within size categories: from $100 to $10,000 for the less than $1 billion companies and from $500 to $20,000 for those with reported revenue of more than $1 billion.

Finally, we divided the sample based on ownership model (public or private) in order to investigate whether ownership type could shed some light on ACT choice. Once again, however, we found that it didn’t. In fact, ownership type explains even less than revenue level seems to do. As Figure 3 shows, private companies have ACTs from $100 to $20,000, while public companies’ ACTs are almost as widely distributed: $500 to $20,000.

WHAT IT MEANS TO YOU

What little we know about ACT to date creates some serious concerns for financial, accounting, and business leaders because:

- It makes benchmark comparisons of companies’ reported net income within the same industry very risky.

- It diminishes the utility of commonly used reported net-income-based financial ratios and performance measures.

- From an internal control perspective, geographically far-flung business units may take liberties with respect to ACT period-to-period consistency to boost their reported earnings.

- It may tarnish the credibility of professional accountancy, including the way the public views the accounting profession and business in general. The financial statement user community relies on the accounting profession to provide financial information that is comparable across companies in the same industry. Significant variation in ACTs across an industry that impacts reported earnings could reduce the credibility of the accounting profession given that the disclosure fix in the notes to financial statements is so simple.

- It may reinforce the notion that government regulators aren’t effective in looking out for the public interest. For example, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) grants the FASB its financial standards promulgation role. Yet the SEC has issued its own guidance on financial reporting when it has felt it was appropriate. If the SEC didn’t address the ACT disclosure issue if diversity in practice drives a distorted view of reported net income, it could be awkward.

SPEAKING OUT

Participants in our study offered several opinions on the subject of ACTs. Here’s a sample along with our comments about each one.

“Each of our divisions has its own ACT policy.” This practice could make suspect business-unit-level internal/managerial accounting reports, including business-unit profitability measures. There are potential internal control issues as well. Additionally, the Form 10-K consolidation may represent a lack of internal consistency.

“ACT consistency should enhance internal control.” This observation is heartening. The respondent makes the association between ACT practice consistency across the organization and the strengthening of internal control.

“ACT disclosure in general purpose financial statements shouldn’t be required; the analysts already have enough to chew on.” This assertion is an important one to consider. It’s certainly true that those who prepare financial statements have much to contend with these days. For evidence of this, you only need to look at the ever-growing fees that companies pay for their independent audit or even the latest edition of one of the Intermediate Accounting textbooks, which has ballooned to more than 1,600 pages. Nevertheless, one of the key stakeholders, the analyst community, doesn’t view the value of current financial reporting practices uniformly. For example, analysts value segment reporting far more than they do pension and other post-employment liabilities reporting. By this token, the addition of ACT reporting in the Notes to Financial Statements section on property, plant, and equipment shouldn’t be arduous for preparers, especially when you consider the potential value this information may have for people who rely on financial statements.

“We’re reviewing our ACT right now—good timing!” We received this comment and similar ones from several survey respondents. Some say that their ACT hasn’t been reconsidered for more than 10 years. This raises an important point: Wouldn’t it make sense for management to review their ACT convention at least every five years, or sooner if the industry is experiencing significant inflation or deflation?

“ACT disclosure in Form 10-K should be required to improve transparency.” We agree. This proposed disclosure should be a “win-win” for companies, analysts, investors, and the public. Because ACTs are very understandable and usable, disclosure would be a real positive for companies in need of bolstering this aspect of internal control. ACT disclosure would also help remove some of the tarnish that has accumulated on our noble profession and restore its luminous glow.

“Our auditors would have to be lucky to find ACT exceptions.” This comment is concerning but not unexpected. The topic of ACT rarely is covered at the university level, nor has it been the subject of practical research. Though we have no empirical evidence to share on this point, the independent auditor community would be wise to consider what some might perceive as a “sleepy” topic and wake up to the reality that their audit teams may not be applying an appropriate level of rigor to ACT practices. Those in an internal control role should consider the consistency in level of attention to ACT practice, particularly as it relates to the risks associated with increasing globalization, enhanced pressure to reach aggressive reported earnings targets, and challenging business settings with often less-than-mature internal control environments.

“Exceptions to our ACT policy read like War and Peace.” At least this person knows there’s a problem! That’s the first step in rehabilitating the ACT convention in any company. Because a serious number of exceptions to any policy tied to internal control and financial reporting is worrisome, internal auditors should launch a study to find out why these exceptions exist in the first place. This should be done with a view toward establishing a company-wide “no exceptions” or “limited exceptions” policy that aligns with internal guidelines on compliance, ethics, and integrity.

“We have one ACT for IT purchases and another for other assets.” This comment is interesting. Should there be more than one ACT standard within the same company or within different departments in the company? Questions that might be asked include:

- Why does this practice exist, and what benefits and risks are associated with it?

- What problem was being addressed when this practice was instituted?

- Does this practice enhance or reduce internal control?

- Does this practice create any real value to the company as a whole?

- What’s unique or different about, say, IT purchases compared to other asset purchases?

These comments from a representative cross section of finance leaders suggest that ACT research needs to be extended to a larger sample to validate and better understand this significant accounting and reporting issue from a variety of perspectives, including general purpose financial statement reliability, management accounting issues, internal control practices, and the overall goal of enhancing the quality of our contributions to market stability, economic growth, and our professional integrity.

FUTURE CONCERNS

We set out to investigate whether there was comparability in Asset Capitalization Thresholds across companies. By examining a broad range of companies, many similar in size and structure, we found that ACTs aren’t comparable across organizations and, in fact, are drastically different. Dividing our sample based on industry, revenue level, or ownership type didn’t explain this extreme variation.

Our study results indicate real concerns as well as an opportunity to enhance the clarity of reported net income in the context of both management accounting and financial accounting and reporting. We hope to provide more specific guidance in the future.

July 2015